© Warner Bros, 1973

Nothing in film adds an extra dimension to the willing suspension of disbelief than the religious movie. The supernatural comes to life—gods, saints, devils and angels are all possible, as are visits to heaven and hell.

Some writers on this subject come close to equating religious experience—the spiritual—with the cinematic experience. In the sense of this writer they are not equivalent. In fact, the movie is actually a form of expression that lacking in the religious experience by providing image and substance to that for which there is no realistic presence. Religion is a belief in the un-sensed, the unknown and he physically un-experienced. Short of delusion, there is no god, saints or supernatural beings, not Heaven or Hell. The movie creates these images just the way painting and sculptured did before the advent of photography. In the religious s movie—especially where the intent is to evangelize—is intent upon creating the willing sensation of belief. One writer on this subject states that: “Film watching, then, becomes a type of participation in a divine cosmos where the structures of everyday life are rearranged for us in delightful, and sometimes challenging, ways.”* Really? All art is rearranging the structures of everyday life; but if you want to call that “participation in a divine cosmos” you are gratuitously spiritualizing. Still, I would rather go to the movies than to church. This is the same writer who earlier said, in reference to a scene in the movie The Bad Santa: “Snowfall connects the world above and the world below….When it’s not snow, it is some other object or filmic device that brings viewers into the space and time of the film, generally starting from on high, and moving downward, connecting across cosmic orders above and below.” That’s a rather prosaic description of snowfall, again given a metaphysical flair. For religious people everything is metaphysical.”

So I am not here going to admit a religious, spiritual, metaphysical something going on a just about any film—I will be much more obvious in my selections.

[Continued from 104.1]

As with many other things it might have been WWII that played a role in the shift to the darker side of Catholicism and Christianity in movies. The Roman Catholic Church’s reputation did not fare all that well during WWII; Christian countries murdered millions of Jews, and the Roman Catholic Church, often more concerned about the threat of communism than fascism and anti-Semitism, had a mixed record in standing up for the faith to which it owed its origin. Germany is, of course, a Christian country.

But for a time Hollywood concentrated on sure themes in the immediate post-war years. During the 1950s Hollywood returned to the classical religious biblical epics with Quo Vadis (1951), The Bible (1953), The Ten Commandments (1955), and the story of a heroic Jew in Ben Hur (1959). Also, more secular themes were pressing for attention in the post-war years: relations between the genders, The Apartment (1961); the Cold War, Dr. Strangelove (1964); the space race, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); the changing youth generation, The Graduate (1967). Race relations were a highly popular movie theme in the turbulent 1960s. To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), Lillies of the Field (1963), A Patch of Blue (1965), In the Heat of the Night and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967)* addressed different dimension of changing relations that also owed their stimulus to WWII.** The period was also marked with “freedom riders” in the South, sit-ins, school desegregation battles in Southern states, passage of the civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts, and the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King.

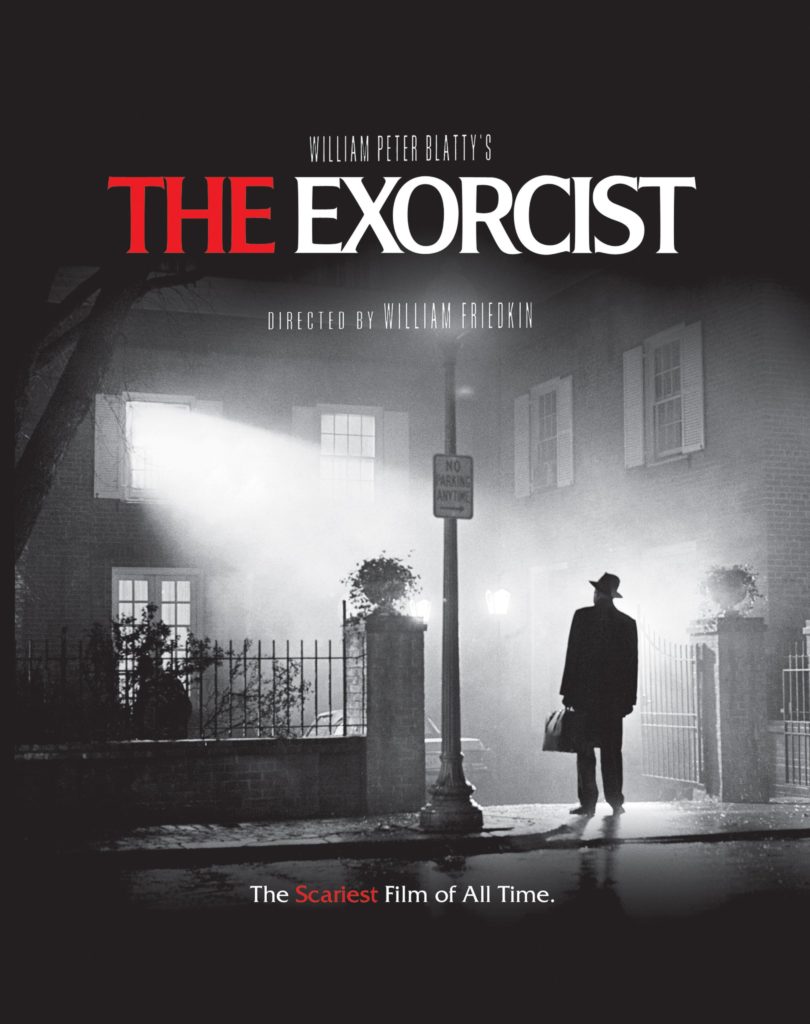

The religious theme, however, began to darken, turning to the evil dimension that has always been a part of metaphysical narratives. Films such as Rosemary’s Baby (1968), about a young woman, Rosemary Woodhouse (Mia Farrow) who, unaware of some sinister plot by her neighbors, is impregnated by some satanic entity rather than her husband and births a demonic child, and The Exorcist (1973), in which a girl is possessed by a demonic force that presents challenges to faith and maternal love and results is a priest’s suicide***; and The Omen (1976) in which the Antichrist is substituted for the child young son of a American ambassador, that initiated a series of films. The dark side of the religious subject might well have owed something to the challenge and mistrust of social institutions in general, as well as the public exposure of the malfeasances of religious institutions such as child sexual abuse and, particularly in the United States, the insurgency of churches into conservative politics.

Religion was no longer a sacrosanct subject. That Coppola could intercut scenes of the baptism of Michael Corleone’s son’s baptism in The Godfather with the gunning down of the crime family’s competitors could be interpreted as the highest disrespect for the Roman Catholic Church’s fundamental sacraments. Scorcese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), adapted from Nikos Kazanzakis’ novel, to the consternation of audiences, portrayed Jesus as a reluctant and confused messiah full of doubts, fears and sexual desires. Even greater objection of the faithful came for the controversial The Da Vinci Code, a mystery-thriller about a two-thousand year cover-up of the Holy Grail, that invited a response from the threatened Church itself and a spate of books objecting to its deviation from scripture. The success of the theme of dark secrets and plots in the Catholic Church was followed with Angels & Demons (2009) and Inferno (2016). Doubt (2008) broached the subject of inappropriate relations between priests and students, as well as relations between priests and nuns, a movie that might have been based on circumstances that occurred in many catholic schools. But by 2015 Spotlight brought the dark secret of the Church not only into the light and scrutiny of in, based on the Pulitzer Prize investigative journalism of the Boston Globe, and Best Picture Academy Award. This time the Vatican did not raise objections to the movie, perhaps determining that matter of sexual predation by priests had already received enough publicity. This was not some abstruse and fanciful confection of the Church’s myths and dogma, but an exposé of a sinister corruption and cover-up that had existed in the institution for centuries. One wonders if the movies had never been invented whether it would ever have been brought to light.

[To be continued]

___________________________________

©2017, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 11.17.2017)

*S. Brent Plate, ed. Film and Religion: Critical Concepts in Media and Cultural Studies. London: Routledge Press, 2017, Vol. 1, P. 6

**Four of these films starred Sidney Poitier.

*** This movie, which did huge box-office, was the first horror film to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture.