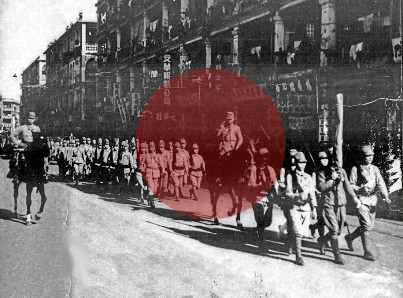

Japanese troops parade in Queen’s Road, Victoria, Hong Kong , December 1941

CONCERTO, a novel by Elizabeth Darrell (1993);

THE PIANO TEACHER, A NOVEL, by Janice Y.K. Lee, (2009)

HEMINGWAY ON THE CHINA FRONT, by Peter Moreira (2006)

HONG KONG HOLIDAY, by Emily Hahn (1946);

CHINA’S WINGS, by Gregory Crouch, (2012);

PRISONER OF THE TURNIP HEADS, by George Wright Nooth, with Mark Adkin (1999);

THE FALL OF HONG KONG, by Philip Snow (2003);

MUSIC ON THE BAMBOO RADIO, by Martin Booth (1997)

“C” FORCE TO HONG KONG: A CANADIAN CATASTROPHE, 1941-1945, by Brererton Greenhouse (1997)

Somewhat in the same manner that fire anneals metals terrible, historical periods seem to have a way of hardening the resolve of cities. The conquered and occupied city must find ways to survive, to persist in the face of subjugation and exploitation. When they do prevail there is usually a new reality and understanding. In the case of Hong Kong, the British were no longer the great protecting overlord. When the local Chinese saw their rulers overrun and paraded in ignominy through the streets and into concentration camps, and that it would take the Americans to finally subdue the Japanese, and that and a new China emergent, there was indeed a new reality. War changes things, nations, people, and cities. The British imperium in Asia was doomed. Two years after the end of the war the “jewel” in Victoria’s was gone.

December 7, 1941, is a day that will always be remembered as a “Day that will live in infamy.” However, most Americans probably have no knowledge at all that just eight hours after Pearl Harbor, the “Hong Kong was invaded by Japanese military forces, a day that in the West almost fell into obscurity. But in contrast to Pear Harbor, the Japanese didn’t just come to bomb and torpedo the British fleet (which had absented itself from Victoria Harbor), they came overland, and to stay. Hong Kong was in orbit of Japan’s “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere,” populated mostly by Chinese (and some Japanese spies) and defended by the “empire on which the sun never set.” Hong Kong had the double disadvantage of being a largely Asian enclave and being the Crown colony of Great Britain, Japan’s enemy by way of its membership in the Axis powers. Japan was picking off the S.E. Asian jewels in the British crown—Malaya, Singapore, Burma, in addition to its treaty ports in China—and the “Fragrant Harbour” was not well-defended. With the German Wehrmacht parked twenty miles off its coast, the Brits had other pressing needs for its men and material.

On December 8, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Army, in conjunction with its assault against Pearl Harbor, invaded the Philippines, Thailand and Malaysia, and Hong Kong. It took only eighteen days of battle for the superior force of two battle-hardened Japanese divisions to overwhelm the weak, undermanned (just 14,000) Hong Kong defenders despite the intense resistance composed of the British Army, Navy and Air Force, Canadians forces, Hong Kong’s own defense force, the Indian Army, as well as many civilians. There was a fierce land battle, with long-range artillery with intense combat at the Gin Drinkers Line, a sort of “Oriental Maginot Line” in the New Territories, as well as the battle of Wong Nai Chung Gap on Hong Kong Island where a handful of defenders took on an entire Japanese regiment.

But some account must be given to the fissures underneath the colonial social foundations of Hong Kong. Snow, who has written the most comprehensive account of the fall of the crown colony, remarks that prior to the war:

For the first time resentment of British rule was becoming detectable in the ranks of the gentry. Wealthy Anglicized Chinese and Eurasians were embittered to find, when they returned to Hong Kong polished by the best education Britain could offer, that whatever their qualifications and whatever their talents there was a level in the local professions above which they would never be permitted to climb. The scales would be tilted against them: if they set up as lawyers, for example, they knew they would have the struggle to win their cases because their British opposite numbers would always be able to hobnob with the British judges in the seclusion of the Hong Kong Club. (P. 20)

Wherever the British stretched the boundaries of their empire they brought their obsessive class system with them. Looked down upon by their brethren back home Hong Kong British were able to look down upon the Chinese (as well as their Indian, Burmese, and Malayan subjects), subordinating them, as they did for example, with such practices as confining them to the lower decks of the Star Ferries. It is reasonable to expect that these and other racial mistreatments led some Chinese to welcome the British being humiliated by an Asian military. Yet, the paradox was that the Japanese behaved with abominable racism toward the Chinese.

The American presence in Hong Kong during the war was minimal. The U.S. administration at the time was in the thrall of the Soongs, especially Soong Mei-ling, Madame Chiang Kai-shek, and hence the Kuomintang. Since the KMT were fighting the Communists as well as the Japanese the U.S. preferred backing the corrupt Chiang, a decision that would haunt Sino-American relations for decades.

That decision would also impact Pan American Airlines, whose William Langhorne Bond had been instrumental in 1933 in the establishment of a partnership with the China National Aviation Corporation (Pan Am owned 55 percent of CNAC), a small fleet of DC2s and DC3s and smaller aircraft that operated routes in southern China from its Hong Kong base.* As recounted in China’s Wings the fleet, often flown by swashbuckling daredevil American pilots became instrumental in flying supplies into Kunming and Chongqing, scraping over the Himalayan “Hump” and jungle canopies to avoid marauding Japanese Kawasaki and Nakajima fighters. Along with the Flying Tigers, they became the stuff of aeronautical legend in China and S.E. Asia.

CNAC turns up again when newly-married writers Ernest Hemingway and Martha Gelhorn who were on sort of a honeymoon-journalistic-espionage assignment in Hong Kong. Gelhorn, a celebrated journalist who was on assignment for a national news magazine was at Hong Kong’s Kai Tak airstrip getting ready to board a CNAC DC2 in the early in the morning of February 25, 1941, to fly up into China, just two days after their arrival. Hemingway remained behind in their Hong Kong hotel where he preferred the booze and schmooze with the local Brits. The famous author was supposedly on a spy mission for the U.S. Government, although at this point his “intel” appeared to deal more with “night soil” and the local cholera break out, especially among the coolies and undernourished than anything else. At this time Hong Kong had no sanitary sewer system. It is unlikely that the two well-known war correspondents would have been U.S. spies, given the other sources of information available. Yet, being celebrities when they did make a trip together into China, they did get to meet figures like Chiang and his wife, and Zhou En-lai (although doubtful at the same time and place), and so were likely debriefed on their return home. Espionage always adds some spice to a story. In fact, the Gelhorn-Hemingway marriage was already on the rocks by the end of the trip, thanks in good part to his alcoholism, such that they returned separately before the fall of Hong Kong to the Japanese.

Southern China was a universe of its own in the years leading up to and during the war, one with enough encounters, cross-connections, adventures and intrigues to fill shelves of memoirs and novels. One of those attracted to Hong Kong at the time was American expat Emily Hahn (she had come from just spending a year in Chungking), author of such celebrated and acclaimed works as The Soong Sisters, China to Me, and long-time New Yorker contributor. Hong Kong Holiday recounts the long months from the Japanese capture of Hong Kong until she was finally returned to the states on an exchange ship.

“Holiday” might at first seem a peculiar term for the title of a story set in a city under the brutal boots of the Japanese military, but Hahn was a China hand rather experienced at outrunning the Japanese from Shanghai to Chungking and finally to Hong Kong, and her chronicle at times seems surprisingly placid and casual. Her descriptions of the daily lives and deprivations of the local Chinese, rich and poor, are rendered at times almost with insouciance, although there were segments of the Western and Chinese population that seemed not overly inconvenienced by the occupation. Despite the dire circumstances Hahn could write of her lecturing at Hong Kong University:

I was in the middle of a fairly credible English lecture next afternoon. . . [and] the three rows of pudding faces had resolved themselves into the usual group of Chinese students, earnest and attentive and just a little inhuman at the beginning of term. Spectacled or spotty, tall or short, all students look alike for about three weeks, and then I begin to know them. By the end of a few months, the picture has become more detailed. There is the shy, clever one, the brazen, stupid one, the one who thinks he is not getting his money’s worth, the one who writes in and asks for a photograph just before the final examination. Some of them cheat. A lot of them are still under the impression that they are in a Chinese-style school where unpopular professors are tossed out on their ears and there is a mad faculty rush for popularity by way of giving good grades.**

By the time she was repatriated by ship from Hong Kong Hahn had a two-year-old daughter by British pre-WWII chief spy in Hong Kong. Unconventional, self-possessed and widely traveled, with a cool-headed knack for survival in perilous circumstances, she might well have become the model for fictional Western women in Hong Kong during the war.

Perhaps it was that many Western women in Hong Kong had to watch their men marched off to POW internment camps that inspired some romantic narratives of life in the occupation years. Elizabeth Darrell’s (the pen name of Emma Drummond, born in 1931 Concerto exhibits a familiarity with the subject comes from her father, who was a member of the British Army stationed in Hong Kong, and where Drummond spent the early years of her life. Concerto is a love triangle hung up on not just on the interruptions of wartime, but that classic British obsession with social class. Australian Dr. Rod Durman and Hong Kong banker’s daughter meets Sarah Channing, an accomplished concert pianist (hence the title, although Darrell doesn’t write well enough about music) who is volunteering at the clinic at which he works. He is about the get a divorce from a marriage gone bad, which adds to the complications of his being of a lesser class and from a commonwealth. Still, love conquers. The third point of the triangle is a dashing British playboy-wastrel. This might be any period romance set in a corner of the British Empire and, eventually, the war conveniently clears away the obstacles to a long-delayed happy denouement. The romance can be set aside in favor of the context that the roles of each of the characters provide, particularly the condition of health care, the deplorable conditions in Stanley POW camp, and the split worlds between those of the “occupied” and incarcerated.

The piano figures, if only gratuitously, in The Piano Teacher.” Claire Pendleton who arrives with her husband in Hong Kong in the 1950s to teach piano to the child of a wealthy Chinese couple and falls in love with their driver, Will Truesdale. Will, a handsome Briton had arrived in Hong Kong in 1941 and fallen in love with Trudy Liang, the glamorous daughter of a Shanghai millionaire and a Portuguese beauty, but their idyllic romance is disrupted by the Japanese invasion when Will is interned and Trudy resorts to collaboration with the enemy. The story is a reveal in which none of the characters are particularly interesting or endearing, a speculation on how war and occupation can seek out the flaws in people, especially privileged colonials and wealthy locals who are brought down when roles are reversed.

There is little wonder that the Hong Kong Chinese called Japanese soldiers law pak tau, Cantonese for “turnip heads,” not the most compelling of epithets. When it comes to exposing the paradoxes, perversities of human relations and the reciprocities of causes and effects there is nothing quite like war in forcing them out into bright light. The Japanese might have justified their East Asian conquests with their alleged concerns for the removing Western colonial influences and possessions from their “Co-Prosperity” sphere, but they were deeply racist in their attitudes and often the brutal and contemptuous treatment of their fellow Asians. One need only research the Rape of Nanking or accounts of the atrocities at Unit 731 in Manchuria to appreciate the hatred of Chinese toward their East China Sea neighbors

Nevertheless, war makes for curious political alliances. There were, in addition to local spies for the Japanese and 5th columnists, also local triads who were allegedly ready to slaughter all Westerners once they were removed from power.***

Wherever they were and whatever their circumstances the British could not help being British, even when being, as this author’s autobiographical account of the cruelty and depravity demonstrated by the Japanese during their occupation of Hong Kong between 1941 and 1945 documents. British military was put to the sword, starved, beaten and humiliated for three and one-half years before the tables were turned and it was the Japanese who were marched in shame through the streets of Hong Kong

Yet, one of the more amusing accounts of the British obsession with social class comes from Prisoner Of The Turnip Heads, which reports that there were some 390 American also incarcerated by the Japanese. The author, a former Hong Kong police officer writes:

The Americans seemed the best-organized entity with a commendable tendency to work together. They buckled down to immediate cleaning up tasks whereas the British community, more divided by class, occupation, and prejudice, spent too much effort and energy bickering or complaining. Not untypical of their attitude was the remark of the rotund British matron who, as she watched a group of Americans repairing a store, remarked, “Isn’t it fortunate that the Americans have so many members of the working class in their camp?” (89)

During those difficult years, there were, as they’re often are in times of war, stories of bravery and heroism as well as atrocities and betrayals. It was no anodyne thing to resist the Japanese military and especially the kempetai, but some did. Martin Booth’s brief story, Music on the Bamboo Radio, of a young British boy separated from his parents and “adopted” by Chinese villagers conducting guerilla operations against the Japanese in the New Territories might, or might not, be based on actual events, but it conveys the dangers and fears that prevailed in the outer reaches of the Crown Colony. Young English boy Nicholas Holford becomes a hero while coming to manhood conducting smuggling and sabotage raids with the local Cantonese resistance.

After three years and eight months of Japanese occupation, Rear-Admiral Sir Harcourt sailed into Hong Kong onboard the cruiser HMS Swiftsure to reestablish control over the colony and accepted the formal surrender of Japan on September 16, 1945. Now the tables had been turned and it was the Japanese who were being marched down Queen’s Road in defeat and it was Japanese who were incarcerated in Stanley Jail. War crimes trials, adjudicated by military courts, began in March of 1946. Surprisingly, aside from some notable exceptions, many Japanese war criminals were given rather light sentences, and some simply disappeared.

The end of the war raised the question of the future of Hong Kong. FDR had favored decolonization, but that notion appeared to end with his death in April 1945. Generalissimo Chiang Kai Shek might have succeeded in turning Hong Kong into what he achieved in Taiwan, but his hands were still full with the Communists. In the end, the British got their Crown Colony back for another half-century. But the sun was setting on the empire on which the “sun never set,” certainly in that corner where the sun rises. Elements in Malaya and Burma had sided with the Japanese against their colonial overlords, India, the jewel in Victoria’s crown, was partitioned and cut loose two years later. Hong Kong Cantonese had seen their colonial masters brought low and humiliated and it was the American atomic submission of Japan that, not mother Britain, that came to the rescue. The Japanese had not been successful in installing themselves as the lords f their new “Co-Prosperity Sphere,” but the war had produced one result in demonstrating the weakness of the West, and resistance campaigns by indigenous Asians had established a latent force for independence.

Because of the yet unresolved matters on the mainland, Britain managed to hold onto its rock while not a Gandhi, or a leftist insurgency, or other more opportunistic entity took advantage; but the underlying ticking clock of land tenure of Kowloon and the New Territories clicked toward the reckoning of 1997. For the time being of another fifty years, Britain would hold a tenuous grip, playing and prospering on a role as the West’s backdoor access to the new People’s Republic of China.

The war also did not show the British in the best light with respect to their own commonwealth comrades. There were instances of stupidity, poor judgment and class bias with regrettable consequences. Notable among these were the ways in which the British—practiced at putting their commonwealth members into the most difficult military positions, such as the ANZACS into Gallipoli and then S.E. Asia—called up ill-prepared Canadian troops to buttress the thinly protected geographic components of Hong Kong.

“C” Force To Hong Kong: A Canadian Catastrophe, 1941-1945 recounts what British commanding officers and the British War Office called a “no military risk” campaign with disastrous results. The book re-investigates the formation of the “C” Force and its departure from Canada to Hong Kong where it arrived just three weeks before the Japanese attack. It outlines the course of the battle from December 8, 1941, until the inevitable surrender of the garrison on Christmas Day. Despite questionable command decisions by British officers, it was claimed by British officers that the Canadians “did not fight well,” an unfair allegation that author Greenhous counters with access to first-hand accounts of battle.

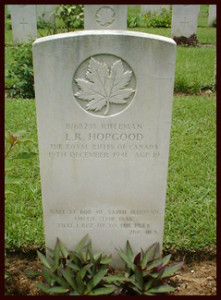

I came close to my own first-hand account of this aspect of the war in Hong Kong. In 2001 I was giving a pre-departure lecture to a group of Americans I was to escort through a three-week China trip when a woman in the group asked me if it might be possible to find the grave of her brother when we arrived to Hong Kong at the end of our tour. She was at least in her late sixties and had not seen her brother since the day he left their home in Eastern Canada in 1941. He was Leslie Hopgood, at the time a nineteen-year-old volunteer in the Royal Queen’s Rifles. Hong Kong is where Leslie Hopgood was headed with the rest of the Royal Queen’s rifles in December 1941.

British War Cemetery, Hong Kong © 2001, UrbisMedia

I was to be in Hong Kong for some weeks before heading to Shanghai to meet my travel group, so there was a chance to investigate if I might locate Hopgood’s final resting place. I began with the Canadian Embassy, which, strangely, seemed to have no records of the locations of its fallen servicemen in Hong Kong. It was the British Embassy, after being routed to several people, that directed me to a Jack Edwards and provided me with his phone number. I left a call with his secretary and was surprised when I got a call back from him in less than an hour.

“Did you say Hopegood, or Hopgood?” he asked me. I could hear some pages being shuffled in the background. “Leslie?” you said?

“Yes, sir, Leslie Hopgood.”

“Right, I have him. Royal Rifles. Killed in action on December 19, 1941. Can’t have been here more than a few days before he went down,” Edwards added matter-of-factly. “I think I could show almost the exact location where it happened. There’s also a Sergeant Clayton, who would have served with him and lives in Canada. Could put you in touch with him if you require more details.”

I was surprised by such accuracy of the information, but told him that I was trying to locate his grave for Hopgood’s sister, who would be in Hong Kong in a few weeks.

“Sai Wan Bay War Cemetery, Port 8, Row C, Grave 9 from the Left, go straight down the main aisle from the front of the cross,” Edwards instructed as though he knew the place by heart. He did, and seemed to know everything else about Hong Kong in WW II as I learned in the forty-minute phone conversation that ensued. For Edwards the war in Asia was not the past; he spoke of it as though it had ended last week. He maintained an organization that kept just the kind of records he had just provided me with. He didn’t want anybody to forget what had happened and was somewhat of a fixture around Hong Kong, especially on occasions when commemorative services were held.

In searching for Leslie Hopgood I ended up learning much more about Jack Edwards, a Welshman who served in Malaysia, where the British were also ill-prepared for the Japanese onslaught. Edwards ended up a POW of the Japanese, and he will never, ever, forget, or forgive what they did to him and his fellows. Captured in Singapore he eventually ended up in a POW camp in Taiwan where they were brutalized and forced to be slave labor in a copper mine. They were flogged, starved, tortured, ravaged by dysentery, and died by the hundreds. Edwards stayed in Asia after surviving the Japanese to continue the fight, this time to get the Japanese to own up to their brutality, and get the British to give the POWs and their families the benefits to which they were entitled. It is all recounted in his book, Bonzai, You Bastards! which he wrote forty years after the war.**** It took years, but he was successful in getting the benefits awarded and was himself awarded an O.B.E. for his long service.

The war cemetery is at the east end of Hong Kong island, up in the hills above Chai Wan it slopes down toward the eastern entrance to Victoria Harbor. I visited there before I would escort Hopgood’s sister there a month later, to make sure I knew the way to his grave. As I looked down over the neat rows of headstones, many of them marked “A Soldier Known Only to God,” I had the thought that at least these men who have reposed in this well-kept cemetery for over sixty years had a nice view of the sea. It’s silly metaphysics, I know; but it’s very Chinese, very feng shui and I could appreciate the aesthetic of it. It must be the reason there are so many cemeteries on these slopes. Was that any consolation to a guy who never made it to his twentieth birthday, who has been in this ground since I was a year old, and who will be here forever? Cemetery thoughts.

I was glad Leslie Hopgood, and the rest of these British and Canadian fallen had Jack Edwards to look after them until he joins them (he since has). It gave me a good feeling to see his sister stand tearfully in front of Leslie’s neatly-preserved resting place on that hillside in Hong Kong. Like me, and like Jack Edwards, I suspect that she takes some comfort in that this boy with such a tragically short life will always have a nice view of the sea. I doubt that he had the chance to enjoy it in those very few days in his brief life.

Wars change cities. They are periods of trauma in their life cycles that alter their identities and leave lasting effects. Little remains of the physical reminders of the war in Hong Kong. If one searches there are some gun emplacements and bunkers, or a bullet or shrapnel gouge in a building that has survived the city’s obsessive land use change. Time will further attenuate the city’s memory of the war and only old men will gather in tea houses to recall it through the lens of their boyhood days. The Japanese military is long gone, and now the British as well, leaving the city in yet another conflict over its 175-year struggle with its own identity.

___________________________________

©2005, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 10.20.201)

*CNAC was originally based in Shanghai. Pan Am also flew American passengers into Hong Kong on their famous flying boat China Clippers out of San Francisco, luxurious travel for its time taking several days with refueling stops and hotel stays in Hawaii, the Philippines other Pacific islands.

**(Kindle Locations 185-191). Open Road Media. Kindle Edition. Apparently, things have not changed much with Hong Kong university students.

***Many of the triad members were, in turn, hunted down by the Lam Yi Dui (Chiang Kai-shek’s secret police) who were themselves little more than thugs who executed triad suspects and saboteurs in Hong Kong alleys. There were similar attitudes in Burma, India, and Malaya towards British overlords.

**** Edwards told me during our phone conversation that he could have had his book published by a major publisher if he had been willing to change its title to something less provocative. He refused. As it happens there is a Japanese edition with the title Kutabare Jap Yaroh, which contains a “very rude expletive.”

4 comments

Thanks. WWII history is like a fractal. The more you look, the more there is to see. Endless.

Agreed, Joe. War is also like an historical re-set. Everything changes when we reach the point of killing one another.

A marvel finding Hopgood’s grave with the help of Jack Edwards; write that story.

I agree. But I decided that, in respect of the privacy of his family (which I hope I have not already breached),I would use elements for a fictionalized account (hence not using Hopgood’s real name) that would allow me to address Japanese brutality during the war, while honoring the sacrifice of the fallen like Leslie, and he tormented, like Jack. I have a lot of notes; now to find the time to write it. Thanks for the nudge.

Comments are closed.