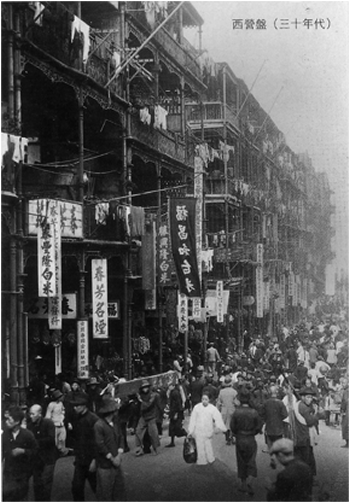

Sai Ying Pun (1930s), neighborhood author lived in 2001

Making a case for a politically independent Hong Kong might seem, at first blush, to contradict geography, ethnicity, and culture—although it is the last of these, that is not determined or bestowed by time and nature, that forms the basis of my brief. Indeed, the first two factors, geography and ethnicity comprise a form of a priori political determinism that I would argue is logically unsustainable, and historically indefensible, unless one subscribes to the brute justification that “might makes right,” or, as Mr. Mao phrased it, that “power comes from the barrel of a gun.” What is to be hoped for here is a “velvet revolution,” one engendered by historical circumstances spiced with a modicum of enlightenment.

But what is likely to occur, given the strategic choices of the essentially “student” movement, is a re-set of something quite close the status quo ante. Making revolution with umbrellas, slogans of peace and love, is not an easy business; it is revolution by annoyance (what I am sure the opposition must have said is “what is to be expected from the kids”). Eventually, they will tire, and need to get back to work preparing for their school exams. They can be “waited out.” They will also make some tactical errors—what was the point of clogging the streets of Mong Kok, a place of local businesses, not the banks and government offices of Central and Admiralty?—and the sympathies of those who need to make a buck to pay the rent will begin to wane.

So there were some bruises and stinging eyes from tear gas and pepper spray, but this has been, thus far, bloodless and not all that disruptive. The PLA didn’t show up, C.Y. Leung didn’t step down, Xi Jinping remains obdurate about rigging the Hong Kong elections, and the Party did a pretty good job and keeping the news contained with its censoring of mainland media. Hong Kong was still pretty much business as usual, and China is still the world’s second largest economy.

The determinist position might be best expressed in the words of Regina Ip, a former colonial official, and now a pro-Beijing member of Hong Kong’s legislature. “The reality in Hong Kong, naturally, is we are part of China,” Ms Ip declares in an interview in the International NYTimes [Oct. 3, 2014, by Michael Forsythe] “You can’t really go against Beijing. These students, you know — all these protests, Occupy Central, class boycott, is not going to move Beijing.” Can you guess what line Ip would be mouthing if the KMT won in 1949?

But it must be admitted that her argument seems almost irrefutable, certainly if you are looking at a map of Asia. There is Hong Kong, sitting right there at the bottom of big mama China. In the logic of geographic “sphere of influence” it seems obvious. But fact is always more complex than diction.

Take this entity called China, for example. Fascinating five millennia history with much invention and creativity and occasional lapses into something that might meet the norms of “civilization” (although hardly any other place qualifies either). For almost all of its history it was a hodgepodge of semiautonomous regions, many with ethnic minorities (some fifty of them) that look more like they belong in a spread in some decaying issue of National Geographic than as components of what the typical prevailing overlord (an emperor, warlord, or dictator) hubristically liked to refer to as “The Middle Kingdom.” For most of its history, China was fractious, bellicose, and backward, with highly localized territorial identities, a “place” of tenuous integrity in spite of itself. How else could the imperial forces of Europe, half a globe from home, manage to wrench chunks of concession territories and trade agreements from this expansive and populous land. China was somewhat like its ideological brother the old USSR, which also was composed of a dominant ethnic center that pulled adjoining ethnic minorities, and even nation-states, into its fold.

It took the Communists, and only after an ejected Japanese invasion and its own civil war, to brutally cobble together the People’s Republic of China. Ripping back Manchuria, ripping off Tibet, subduing the far western provinces, it left Taiwan, Macau and Hong Kong to deal with later, while it caused the deaths of tens of millions of its own people with ignorant, cruel and counterintuitive policies like “The Great Leap Forward” and “The Cultural Revolution.” This was achieved by way of an autocratic one-party system that was heading over an ideological cliff until Mr. Deng found the appropriate verbiage to change the script to “whatever it is, just (and it actually is “cowboy capitalism”) put with Asian values in front of it” and we can claim it as ours. Somewhere between the emperor, Chi’en-lung who told ambassador George Lord Macartney, ca. 1793, that China didn’t need anything that the West made, and the attitude of contemporary Chinese leadership being “but we’ll make it for you—and cheap,” is bracketed the modern economic history of The Middle Kingdom.

This is all history familiar to anyone who has bothered to read the first couple of paragraphs, but I thought it necessary as preamble to the point that, historically, China is as much a “made up” place as Hong Kong is a borrowed place and, as a place with political stability and territorial integrity a quite recent nation-state. But now China is big, and powerful, with an autocratic government in power for sixty-five years of mostly devastating governance by authoritarian paranoia. That paranoia—that not every region, minority, or formerly independent state that happens to be within its grasp and is easily defined as Chinese, wants to be the People’s Republic of Chinese.

In fact, the historical circumstances are such that it can be validly argued that a separate, and distinctive, culture has evolved in Hong Kong, a fusion of East and West, generational experience with civil liberties, education and economic policies, its own unique movie industry, far superior to and more expansive than their northern cousins, and its own language and cuisine.

Although the acquisition of Hong Kong from China came about as a result of the employment of imperial force from British trading companies, the fact is that the China of the mid-19th Century was a vastly different China than was established through the process of civil war in the mid 20th century. As exasperatingly bigoted as the British can be (and were) they managed to conduct the development of the Crown Colony without the mass starvation and other miseries the PRC inflicted on its people. Most Hong Kong Chinese are more aware than their northern cousins that Mao Zedong is right up there with Hitler and Stalin as the deadliest dictator of the 20th Century. Even the brutal crackdown in Tiananmen Square in 1989 is annually commemorated by Hong Kong people, while it has been all but expunged from the historical record and contemporary media by the PRC government. Most of the demonstrators in Central and Admiralty are well aware that they are far better off in a faceoff with their own police than with the PLA.

The young demonstrators of Hong Kong can already sense the juggernaut of the PRC will absorb and overrun their unique culture and their sense of place. The Brits might have run the place from London, but they needed Cantoville to make it work. And the Brits were Western, gweilos, a clear and unambiguous racial and cultural distinction; not so with the northern cousins, whose origins, language and culture can more readily obliterate by absorption Hong Kong’s indigenous culture. Consequently, one perceives that there is a sense of desperation in the push of Hong Kong’s youth for democracy. In a democracy—at least at its ideal—numbers count. At present, the seven million or so Hong Kong people “have the numbers.” If democracy were installed, to exercise some control over their fate. But numbers can change fast in China. A few decades ago Shenzhen, immediately to the north, wasn’t much more than a fishing village; today it is as large as Hong Kong. But, of course, in the prevailing a one-party, centralized, authoritarian political system, numbers don’t matter. What matters is any threat to that system.

[To be continued]

___________________________________

© 2014, James a. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 10.8.2014)