The world knows that people were murdered at Paris cafés and other places this past weekend. Much has been said and written, and will be, about these horrific events, but I want to say something different just now about Paris cafés, about what they mean to the urban culture of the city, about what they have meant to so many others who have lived and worked in Paris, and what they have meant to me. The following is excerpted from my book, Mon Cahier de Paris: Café Writings, 1989, 1999, (UrbisMedia-Ltd., 2015)

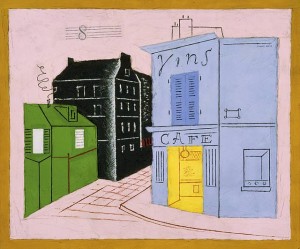

Stuart Davis, THE BLUE CAFÉ (1928) Art© Estate of Stuart Davis/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

You start at a café table because

everything in Paris starts at a café table.

Irwin Shaw, Paris! Paris

Sidewalks are the living (or dead) reefs of the city’s biosphere. They connect, and transition the city’s movement, its ebb and flow from the street to adjacent land use, from curb to shop and café. They are the zone of most intense social interaction, where the refreshing currents of traffic and pedestrian movement nourish social interaction, commerce and propinquity. By day they flow with the busier circadian rhythm; by night the ambient glow from café and shops highlights the more sedentary life of the reef that can extend from the early evening to the early hours of the morning.

Following their first appearance in Italy in the 1660s cafés began to sprout up everywhere in Europe and England. Almost immediately they became popular literary, social and political gathering places that fostered such freewheeling discussion that civil authorities often viewed them with alarm. In 1675, Charles II closed three thousand coffee houses in England, citing them as “seminaries of sedition,” but rescinded the edict a few days later because of public pressure.

The association of the café with the word, written and spoken, sedate and seditious, is firmly established. Boswell listened attentively to Dr. Johnson in London’s café’s; later, Wilde and Whistler matched wits at the Café Royal; the patrons of Rome’s famed Café Greco included Goethe, Keats, Shelley, and Lord Byron. Lenin and Trotsky plotted and penned manifestos in Geneva’s Cafe Landolt, and Tristan Tzara founded “Dadaism” is Zurich’s Café Voltaire. Freud was a regular at Vienna’s Café Landtmann. Madrid’s Café Gihon, Berlin’s Romanishes Café bombed out during the war, and numerous other cafés from Istanbul to Greenwich Village have functioned as substitute homes, meeting places, and reading rooms, for the famous and anonymous for nearly three-hundred years. The association between coffee and creativity is well-documented by Budapest’s flamboyant New York Café, best known among the city’s six-hundred cafés, as the gathering place for several of Hungary’s famous scientists (Leo Szilard, Edward Teller, Eugene Wigner), political intellectuals (Arthur Koestler), photographers (Robert Capa and André Kertesz), and motion picture luminaries (Michael Curtiz and Alexander Korda).

Few cities rival Paris in this regard and much is owed for the richness of its urban reefs to its cafés. Café Procope first opened its doors in 1686 and established the relationship between coffee and revolutionary thought and action with a clientele that included Voltaire, Franklin, Jefferson, Robespierre, Danton, and Marat. Besides the 18th Century Who’s Who of sedition and political schemes there were literary luminaries Georges Sand and Alfred de Musset and even scientists; Alexander von Humboldt reputedly took his lunch at the café in rue de l’Ancienne Comédie every day from eleven to noon during the 1820s.

By the mid-1840s there were over three thousand spread around the city, such that Jules Michelet could write “Paris becomes one great coffeehouse . . . [where] wit sprang forth, spontaneous, where it might as it could.” By then, cafés had become the most popular public venue ranging from a place of solo quiet repose or meditation, to social engagements from a lovers’ rendezvous to seminars of intellectuals and cabals of political intrigue. In the late 1860s at Café Guerbois one might find Edouard Manet, Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir, at the time known as the “Batignolles Group,” in spirited discourse over the a new approach to painting that would rename them as them as “Impressionists.” Café life itself would provide much of both inspiration and subject matter.

“Does black coffee make you drunk, do you think? I felt quite envirée… and could have spent three years, smoking and sipping and thinking and watching the flakes of snow. Then you know the strange silence that falls upon your heart – the same silence that comes one minute before the curtain rises. I felt that and knew that I should write here.” So wrote Katherine Mansfield, in a letter to John Middleton Murray, on March 19, 1915, three years before they married.

Years later, cafés would play a strong role in the relationship between Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin. They often wrote to each other on café stationary, as Miller did to her in 1932: “This afternoon I was reading [Proust] in the Café Mirroir . . . From time to time I looked up and allowed my eyes to rest on the string of café crèmes that run from one end of the hall to the other.”

Another pair of famous café lover/writers met and wrote in a café. Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir practically took up residence at the Café Flore, where the owner installed a private phone for their convenience. The war caused them to be separated, but she still wrote Sartre in 1941: “I’m upstairs at the Flore and it is seven in the evening. It’s agreeable because you can hear all the people swarming beneath you, yet you’re totally peaceful.” Two years later he was there, and wrote, with the same simple assurance that she would be able to imagine being there: “ It’s five o’clock, it’s Saturday, I’m upstairs at the Flore, the sun is coming in the windows.” It goes unrecorded what Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai thought of the noise or light of the Flore when he was among its clientele in the 1920s.

Many Paris cafés were made famous by their favorite patrons, or vice versa. African-American poets, writers and performers such as Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Richard Wright and Josephine Baker, might be found at La Coupole. Artists Modigliani and Giacometti often took their caffeine at Le Dome, and photographers Eugene Atget, Edouard Boubat and Robert Doisneau frequented Les Deux-Magots. Hemingway, in A Moveable Feast, recollects: “I came to a good café that I knew on the Place St-Michel. It was a pleasant café, warm and clean and friendly, and I hung up my old waterproof on the coat rack to dry and put my worn and weathered felt hat on the rack above the bench and ordered a café au lait. The waiter brought it and I took out a notebook from the pocket of the coat and a pencil and started to write.”

These days one is likely to observe a patron texting or emailing from a Paris café. But most writers and artists got around among Paris’ cafés, seeking inspiration or contemplation, privacy or conviviality, and always a vibrant changing perspective on the movements of the urban reef. It could hardly be better said than, as Sartre did in Being and Nothingness: “It is certain that the café by itself with its patrons, it’s tables, it’s booths, it’s mirrors, it’s light, It’s smoky atmosphere, and the sounds of voices, rattling saucers, and footsteps which fill it—the café is a fullness of being.

“A walk about Paris will provide lessons in history, beauty, and in the point of life,” remarked Thomas Jefferson. Of course, Jefferson got off those streets and was back in Monticello just before they began to run red with the blood of the Revolution. Even at a distance, and being an anti-monarchist, the Revolution soured him on Paris. “Great cities are a sore upon the body politic,” he wrote.

All that aristocratic blood has since been washed away (occasionally by yet more blood) since those revolting days. These days we find some of the greatest praise for Paris given to these same venues that witnessed the Reign of Terror, the lives of Les Misérables, and the drumbeat of Nazi jackboots. Jefferson was right about the history lesson. “Paris was a universe whole and entire unto herself, hallowed and fashioned by history; so she seemed in this age of Napoleon III with her towering buildings, her massive cathedrals, her grand boulevards and ancient winding medieval streets – as vast and indestructible as nature itself,” enthused Anne Rice without ever mentioning a vampire despite the reputation of those sanguineous thoroughfares. Anais Nin concurs: “Each stone [in Paris] has a history, and each street bulges with lives well-lived, deeply loved. . . . It is. . . the capital of intelligence and creativity, enriched by the passage of all the artists in the world.”

What other city could have its own mot juste specifically for urban perambulation. “Paris… is a world meant for the walker alone, for only the pace of strolling can take in all the rich (if muted) detail,” wrote Edmund White in his aptly titled “stroll through the paradoxes of Paris,” The Flâneur. Margaret Anderson probably qualifies as a flâneur (or someone who works for the Paris Tourist Authority) when she writes that Paris . . . “is the only city in the world where you can step out of a railway station—the Gare D’Orsay—and see, simultaneously, the chief enchantments: the Seine with its bridges and bookstalls, the Louvre, Notre Dame, the Tuileries Gardens, the Place de la Concorde, the beginning of the Champs Elysees—nearly everything except the Luxembourg Gardens and the Palais Royal. But what other city offers as much as you leave a train?”

Kate Simon offers “A final reminder. Whenever you are in Paris at twilight in the early summer, return to the Seine and watch the evening sky close slowly on a last strand of daylight fading quietly, like a sigh.” No doubt then you are likely to agree with Turkish playwright and novelist Mehmet Murat ldan “If you have ever walked in Paris, you will see that Paris will ever walk in your memoires!” And what more romantic way to remember our meander through the streets of Paris than in the lyric of Oscar Hammerstein, with a melody most appropriately recalled in the tones of a concertina: “The last time I saw Paris, her heart was warm and gay/ I heard the laughter of her heart in every street cafe.”

I couldn’t have said it better myself . . . but it’s always worth a try.

You end at a café table because

everything in Paris ends at a café table.

Irwin Shaw, Paris! Paris

___________________________________

©2015, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 11.17.2015)