The Tomb of Anwar Sadat, Cairo ©1991, James A. Clapp

When I mentioned to our driver, Hisham, that I could swear people were getting laid all over the Great Pyramid of Kufu he seemed unimpressed. It may have more to do with the fact that the pyramid provides some privacy in a country that is so crowded he offered. Moreover, the Egyptians are hardly daunted by any memento mori . A couple of days earlier I had wandered through the huge City of the Dead near the Khan al Khalili bazaar in which thousands of squatters have made homes in the mausoleums of the dead. In a place where the past is so woven into the present there is little wonder that the dead must make way for the living.

Nor was there little wonder that rather lascivious thoughts took their place alongside my marveling at this special night. Sitting on the huge blocks a just a few courses up laid down five and a half millennia ago, and looking out toward the Nile and the lights of Cairo, I could not help contemplating what it would be like to climb all the way to the top with an adventurous lover and give a whole new connotation to ‘harmonic convergence’.

Hisham’s thoughts however were running to refreshment, and after a good soaking up of the atmosphere of the world’s most famous necropolis, he said the word I didn’t want to hear for a month or two: shay. The mere though of more tea constricted my bladder. Furthermore, it was around 3AM.

“I think you will enjoy this café very much, Dr. James,” Hisham said confidently. He already knew of my penchant for cafés that had some historical connection or another. A couple of days earlier I had asked him if there were any interesting cafés nearby the Hilton and he had recommended Groppi’s at the Midan Talaat Harb . Groppi’s is known for its excellent confections, but also has a reputation as having been the scene of intrigue during WWII when spies for the Germans and the English and Americans kept tabs on each other over cups of tea and thick coffee. It still has its metal topped tables and the somewhat derelict appearance of a place that could ‘tell stories’.

When we made a visit there a few days earlier Jack and I ordered mint tea and some pastry. As the waitress served it to us I happened to notice a large cockroach crawl leisurely across her shoe. When it touched her skin she looked down, calmly stamped her foot with just enough force to dislodge the insect, and with a second quick and skillful tap, dispatched with a ‘crack’, but not a splatter. A third expert foot movement flicked the corpse out of sight under the table pedestal. A ballet aficionado would have seen the moves as a well-executed ronde de jambe . Without changing expression she placed the bill on the table and walked off. In old cafés that serve pastry and espionage it’s a good idea that even the roaches stay “undercover.”

So when Hisham led us through an underpass in Khan al Khalili that was crammed with squatters, screaming children, beggars, and piles of refuse, and then through the narrow streets to el Fishawy Café I was already beginning to feel like Indiana Jones or a character out of some spy novel. It was nearing 4AM now but I was exhilarated by the prospect that I might get to meet Egypt’s Nobel Laureate author, Naguib Mafouz. Hisham had remarked that the writer was a regular patron. Moreover, the story on the café was that not only that is has been owned by the same family for three hundred years, but also that it has never been closed during that time.

Still, three centuries is a rather brief period of years for a country like Egypt. The area of Khan al Khalili, while it might appear ancient to Western eyes, is actually part of “Islamic Cairo”. The nearby Al-Azhar Mosque is, for example, a relatively ‘young’ structure from 970AD (it also boasts the world’s first ‘university’). The bazaar began as a caravanserai as “recently” as the late 14 th Century. Today it is an immense souq of shops, small industries, mosques, mausoleums and madrassas , and restaurants and cafés.

El Fishawy looked like it had been there at the beginning. Rickety wooden chairs and small, square tables were arranged on a wooden floor that looked like it hadn’t been swept in three centuries. The dimly lit café seemed like a set from a movie. All of the patrons at this hour were in gallibiyyas, some were wearing traditional Arab turbans, many were smoking from shishas , the water pipes with little smoldering mounds of aromatic tobacco on top. The exotic and mysterious atmosphere was thickened and enhanced by old framed and blemished mirrors that hung out from the walls at angles that created a kaleidoscope of reflections and made the place seem even more crowded. We watched and were watched in their reflections.

Waiters passed among the tables with trays of dented metal teapots and chipped and cracked crockery. I had to drink left-handed from my cup to avoid the serrated chip on one side of its lip. A din of Arabic, clicking cups and saucers and gurgling shishas composed the ambiguous sound track. Jack and I were the only Westerners I could see, and were it not for Hisham’s Western dress it seemed as though we had fallen through some time window to several centuries earlier. Everything seemed to be 300 years old!

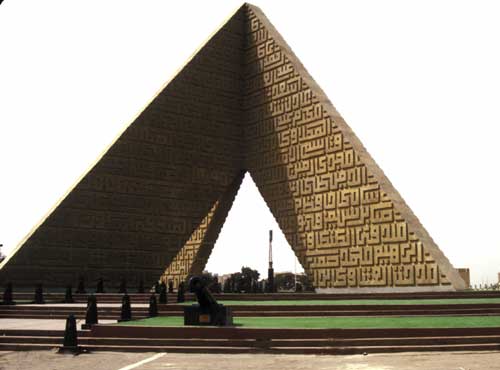

But where was Mafouz? Hisham made inquires on my behalf and we were disappointed to learn that this was not one of his regular nights. Perhaps it was just as well; I had read only one of his books and was saved from making a fool of myself. It was a couple of years later when I read in the paper that he had been attacked by a Muslim extremist and nearly killed by knife wounds. Fame, literary license and regular habits can be a dangerous brew. I wonder if he will ever feel safe again to wander through the bazaar to his favorite café. Egypt has never been an easy place for pharaohs and politicians—a few days earlier I went from Tutankamen’s sarcophagus in the National Museum to where Anwar Sadat had been gunned down for making peace with Israel—and now its extremists were attacking its artists and intellectuals. Not long after I left the country tourists would become the target.

The morning light was just coming up when we were leaving el Fishawy ; the fasting of Ramadan would begin again. Back at the Hilton I slept soundly and dreamed of the pyramid of Kufu. In the morning we would pass by them again, on our way to Alexandria. My notes for the script were fragmentary and tentative, with marginalia about death and love on the cool stones of pyramids. It makes one feel so “temporary.”

Driving northwest I reflected that it’s a rather upside-down place, Egypt. What they call “Upper Egypt” is really the Southern part, closer to the source of the life-giving Nile. “Lower Egypt,” in the Northern part, where the fertile delta and most of the population and economy of the country is, hardly seems “lower”. During Ramadan , the customary activities of day and night are reversed. The country’s prime livelihood is in marketing a long-dead civilization of the past, while the present Egypt is in cultural turmoil over whether it should pursue modernization and risk all the social upheaval that might bring, or follow the reactionary course of some of its Middle Eastern neighbors.

History will sort it out, but the pyramids have seen it all before.

___________________________________

©2004, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 5.11.2004)