An encounter with the Chinese English teach in Wuhan, China in Part I inspires a recollection of childhood days:

My favorite playmate when I was a little boy was my grandfather, Sebastian. He was also my first traveling companion. I’m convinced that my relationship with him is the reason that wherever I travel I am fascinated with old men idling in cafes, sitting on benches in parks, or watching the theater of the piazza. I always wonder what memories are playing in their minds as they sip their espresso or wine, argue with their cronies, or gaze wistfully upon some passing beautiful girl.

Sebastian is long gone now and I, myself now a recent grandfather, have him only in memory. But he comes freshly to mind, often bringing a smile to me, whenever I see some old guys playing petanquebeside a café in the south of France, or sitting in the shade of a pepper tree outside a kapheneion in Crete, or slapping down mahjong tiles on a park table in Wuhan. That’s when I can vividly recall my grandfather playing cards with his old country buddies in that neighborhood bar back in Rochester in the early 1940s. I’ll never forget the name of that bar either, The Knotty Pine, because my grandfather never stopped mispronouncing it as the K’noddidy Pine.

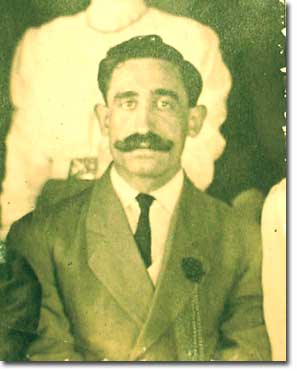

Sebastian Bianchi, ca 1900

Sebastian would bring me there almost every day before I began school. I sat on the floor, my toy truck making and unmaking piles of sawdust and cigar butts, listening to the Abruzzese-accented Italian of their gesticulated discourse. They gibed, joked, and, of course, told each other those embellished stories of their youthful exploits old men everywhere tell.

Then, of course, my curiosity about old men’s memories was unformed. All my life lay before me, as did those encounters and events that would form my own memories. Faraway places and peoples, passions, loves, lost loves, victories and disappointments, were yet to come. But at that time I was fascinated with who I thought was the best playmate and travel-companion a young boy could have: Sebastian Bianchi.

I also had no idea then that these childhood experiences would factor into my subsequent interest in travel and, more particularly, the way in which the experience of travel, especially the introspection it can bring, would have their origins in that eccentric wizard of a grandfather. Little inkling did I have that one day, in some faraway place, in seeking Sebastian out in the form of some old gent leaning on a cane, or staring into the middle distance of some memory, I would also be venturing into my own existential territory.

Sebastian’s own travels were not very extensive; thirty or so days in steerage from Civitavecchia to New York in the last decade of the last century. His story is an oft-told tale of immigrants from all over Europe: slim prospects for his hunting and farming skills in the big, foreign city, but a strong back and a will to ruin it with hard labor to make a stake to take back home, or buy into America’s dream. He told his own version of the old immigrant’s story. “I came to New York because in the old country I heard that New York streets were paved with gold. When I got there I discovered three things: the streets were notpaved with gold; the streets were not paved at all, and; I was the one who was going to have to pave them.”

Sebastian paved streets in New York until he nearly sliced up a non-Italian supervisor who kept pronouncing his given name in a way that he, perhaps intentionally, intoned too close to the Italian word for “bastard.” Shortly thereafter, and perhaps because he had a brother living up in Rochester, he headed upstate. He might have returned to Italy after building a nest-egg had he not met the beautiful Loretta Corona.

Why my grandmother married Sebastian has always been a source of wonder in my family. The daughter of a middle-class family, also from Abbruzzi, that owned a tile-making factory, she had come over to upstate New York not to immigrate, but to visit relatives. But something in the wild and dapper countryman, who probably wouldn’t have had a chance with her in the old country, caught her fancy. Neither of them ever went back, or ventured more than a few miles from their new American home.

They were an unlikely couple. The wedding photo of them shows my grandmother in the contemporary “Gibson Girl” hairdo and high-collar, but her stunning, classic beauty would turn heads in any age. Her face features the same huge, light-blue eyes set in cream skin that turned up two generations later in my daughter Lisa. Beside her in the photo is the droopy-mustachioed, wiry, Sebastian, wearing an almost fierce glare on a face with a mashed, Michelangelo-nose that betrayed the wages of a quick temper that would turn up again in his admiring grandson.

My parents and brother and I lived in the same house with my maternal grandparents, as did two other families of relatives. My grandmother was a saint to me, and to everyone who encountered her. She was beautiful, loving, and strong. Her legs had been badly burned in a religious bonfire back in Italy, but she gave no sign of the pain that lingered in them, preparation perhaps for the courage with which she faced a painful death.

I could do no wrong in my grandmother’s eyes. I was her first grandchild, to be coddled and cosseted, and made to feel like I was being groomed for some special destiny. In the evenings, after the dinner dishes had been put away, she would sit in a soft chair in the corner of the darkened dining room. Only the light from the dial of the radio would cast a sepia nimbus around her face. It was 7:30PM and Fr. Ciccignioni, from Sts. Peter and Paul was leading the nightly rosary. If I happened through the dining room, which connected the parlor to the kitchen, she would summon me:

“Jeemee, Jeemee, vene qua , vene qua, caro mio. ” I would climb up on her lap for a few “Hail Marys” until I squirmed too much and she would release her embrace. My memory can still summon her earthy aroma, and soft, warm flesh. She was the Madonna incarnate.

At such times my grandfather was usually in the kitchen with a bottle of “klu-klu”. If the were an occupation called “onomopietist” Sebastian would have been a master. “Klu-klu” was his term for a bottle of whiskey, because that was the sound it made when the first few ounces were being poured out. Whenever I pour from a new bottle and it makes that sound, I think of him.

Since Italian was his first language, he figured that creating neologisms from the sounds that things made was an appropriate intermediate language. For much of my youth “klu-klu” meant liquor. He also coined the word “keek-a-da-geee,” which I still regard as a much more appropriate term for a rooster’s “coxcomb.” Moreover, when you said, rather called, “keek-a-da-geee,” you were supposed to put your hand above your forehead, fingers pointing skyward and front to rear, spreading them as you trumpeted: “keek-a-da-geeeEEE, keek-a-da-geeeEEE!” It always made perfect sense to me.

But these “linguistics” were only part of an original and mischievous personality that would capture the imagination of a little boy. What little boy would not be transfixed by a basement wonderland that, scattered around fermenting wine vats, where boxes, drawers and shelves bursting with tools, toys, found objects, things thrown away by others but treasured by little boys and at least one old Italian man. What possibilities to carry-out all sorts of boyish fantasies.

There was that summer day—it had to be after 1945 because my uncle was home for good from the war, and had brought a few souvenirs—when I discovered in a box in that basement a starter’s cannon. Where, or how, my grandfather acquired a foot-long brass cannon on a little wheel carriage, that was perhaps used to start off yacht races, I will never know. Of course, it was designed to make only noise, not war; but that didn’t stop my imagination, nor my grandfather’s delight at a chance to please his grandson.

And so, as I looked on like a rapt pupil, Sebastian drilled out the bore on the cannon to accept a ballbearing about a half-inch in diameter. Here one of my uncle’s ‘souvenirs’ came into play: a clip of 30.06 rifle shells from which my grandfather extracted some gunpowder. Take a fuse from a cherry bomb found in another drawer, drill a flash hole for it, and we were ready for battle.

Ten minutes later we were cowering in that basement hoping any knock on the door wouldn’t be the police. Actually we were in my grandfather’s private toilet, a sanctum sanctorum he had built for himself, a cozy little place with walls covered with pictures of bosomy 19 th century French postcard girls and, for some reason, a large photo of Pope Pius XII. It was a privilege to be allowed into this private domain.

The cannon, which we had placed on the back of his tool shed on the alley behind the house, almost killed us. The charge was way too much and the ballbearing blew out a bedroom window in the house on the other side of the alley. The recoil on the cannon threw it back up against our house. The wonder is that it didn’t just explode and kill us both. But part of our shaking down there in the dark toilet room was from the thrill of the danger, as well as from our fear of the police that never came.

To all the women in the family, my grandmother, mother and aunts, Sebastian’s facility with firearms—the makeshift artillery excepted—was a source of ongoing exasperation. My grandfather was a hunter back in the old country, and still was, in his 70s, a crack shot with a rifle. But he lived in the middle of the city now, and at least at that time there were not many guns in the city.

So when he concocted his little plan to exterminate the large brown sewer rats that were knocking off his rabbits, he got us in hot water again. This time he hung ears of corn on strings from the gutters of the garage until they dangled about a foot above the ground. At dawn he and I were in the back upstairs bedroom, the .22 caliber rifle loaded and propped on the sill. Like Sergeant York he picked off one rat after another as they reached up to pull down the corn. He let me fire coup de grace rounds into a couple that were still squirming.

He caught hell for that from the women, but they also eagerly ate his delicious rabbit a la cacciatore , which he told me was chicken. I never suspected anything when, periodically, he would announce that the rabbits had dug under their pen and escaped, or that the rats got them.

That faculty for the good story, even if it is a good ‘cover’ story, made him all the more engaging and interesting. The Italians have an exculpatory saying, that “it may not be true, but it’s a good story”.

He would tell me about his youth in the Apennines, of the animals he shot, and cooked and ate. “But no snake,” he would say. He would eat anything but snake. Anything, even starlings, those scavenger city birds. Here again I was invited into Sebastian’s world of the man-boy. In the white winter snow of our backyard lay a box the size of a casket. “Casket for bords ,” he would say gleefully. The hinged lid was actually a screen, and this was propped up with a stick so that the starlings could settle into their “casket” to feast on the garbage my grandfather had laid out for them. A rope tied to the stick ran from the box, across the back yard and through a hole drilled in the frame of a basement window. When the casket filled up with starlings he would let me pull the rope that dropped the lid. There was a little door on the side of the casket to allow him to reach in and wring their little necks. They were delicious, cooked in his patented cacciatore sauce.

Usually, after one of his meals, he would bring out his bottle of “klu-klu,” and for me and my brother and cousins, he would place little bottles of “klu-klu” on the table. We each had our own bottle—little bottles that had contained the flavorings he used when he made his liquors—and now were refilled with watered down anisette. We would sit around the table, pretending to drink like men, listening to his stories of the old country, neither suspecting, nor caring, that they might not be completely true.

I never saw him drunk, and not one of his grandchildren has a problem with alcohol. Not that he couldn’t put the stuff away with the best of them. He regularly greeted our mailman, whose name was also Bianchi, with a couple of shot glasses of one whisky or another. They would toast the good name of Bianchi and the mailman would immediately set off on his rounds, to the disappointment of Sebastian who for years wanted to have a long chat with the mailman. No matter what my grandfather served, whether scotch, bourbon, rye, gin, the mailman downed it briskly, said grazie tante , and departed. Except the day my grandfather served him a little something special he imported from Italy. Centerba 72 it was called, a mean, green, throat-burner supposedly containg “100 herbs” that Sebastian claimed would seek out and destroy any germ that dared to invade your body.

I was told later by my uncle that Dom, the mailman, downed his shot of Centerbe 72 that day, turned without saying his thanks, stopped at the edge of the porch, turned back to Sebastian, opened his mouth and tried to say something. His eyes were watery and the sound was just a faint, hoarse, whisper: “Aqua, . . . aqua ,” he said pleadingly. My grandfather already had the glass of water ready. That day the mailman talked.

That resourcefulness, even if occasionally laced with mischief, was so much of the legend of Sebastian. To a young boy his abilities were almost heroic. He was an accomplished tailor and shoemaker, he made his own wine (which was his one great failure because it was like battery acid), his own sausage, herbs, and liquors. He could grow anything and cook it. He once discovered a crack in the plaster in the kitchen. His carpentry skills were so good that when he found some dry rot behind it he knocked out the whole section and there was a complete window in its place a few hours later. Never mind that my grandmother didn’t want a window there. Why didn’t he put it where the light would shine on the counter, she demanded?

“But that’s where the dry rot was,” he countered.

Sebastian never had a regular job from the time I was a child. But that never seemed odd to me, his job seemed to be being my grandfather-playmate. He was also my first tourguide. He loved to travel about the city and parks, and outlying wooded areas especially seemed to appeal to long forsaken mountains in Abruzzi.

But his mountain-man background never seemed congruent with my grandfather’s sartorial attitudes. No one in my family can recall his ever leaving the house in anything but a suit, tie, glistening shoes, and his fedora. The suits and hats were always in seasonally appropriate styles and colors, and always cleaned and pressed. With his twig-like Di Nobili cigar in his teeth he was a dapper boulevardier worthy of a Fellini film.

He insisted that I also be well-dressed when we went on our excursions about the city and environs. These were always on public transit, busses or subways. He may have been dressed like he owned a car and a chauffeur, but he was a confirmed transit rider with a bus and subway pass and I trace my own preference to riding these modes in any city I visit back to those days. We would often ride to the park and walk along the river, stopping to watch the old Hasidic Jews fishing for carp with dough balls on their hooks. As usual he would have stories of the old country, of getting into and out of trouble, hiking and hunting in the mountains he would never see again. He would tell and retell them as we walked along the tree-lined riverbank, only breaking the stories when—and to my mother and aunts’ consternation when they learned of it—we stopped to pee together into the river.

Even in later years as he grew feeble and I, being a student, had less time to spend with him, the Sebastian legend grew. My school buddies all wanted to meet the guy who, fully dressed in his suit and hat, rode the bus from the inner city to my parent’s house in the suburbs where we had moved when I was a teenager. It was his second trip of the day, because earlier he had come to visit my mother who was doing laundry in the basement and did not hear him come in to our large backyard that backed up to woods. There he spied a flock of pheasants rooting around in the carpet of autumn leaves. He turned around, bussed back into the city, grabbed his rifle and a bandoleer of ammunition and rode back out to our house. The first my mother knew of his presence was when the first shot took the head off the first pheasant. He caught holy hell for that one, and became the hero of my buddies as well.

I’ll always have his stories, but I still miss Sebastian. I suppose that’s why I find myself always looking for him in the eyes of those old Chinese guys, or old guys wherever I travel.

In the years before his death he would often come to my parents’ yard and sit quietly with that gaze into the middle distance of memory in his eyes. He would doze in his suit and hat, but mostly peer into the woods, perhaps remembering those pheasants, perhaps pheasants in those hills of his youth in Italy. At times he would get a little smile, just as I do in writing about him.

___________________________________

©2004, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 7.16.2004)