“The sun,” it used to be said, “never set on the British Empire.” Somewhat the same might be said of the sunlight that streams through my window onto my bookshelves. Chances are it will illuminate a title that is about, or was influenced by the British Empire. After all, I reside in a former British colony.

“The sun,” it used to be said, “never set on the British Empire.” Somewhat the same might be said of the sunlight that streams through my window onto my bookshelves. Chances are it will illuminate a title that is about, or was influenced by the British Empire. After all, I reside in a former British colony.

I think it was Tarzan movies that got me hooked on British imperialism. It was at its most molecular and most fundamental when British-accented Jane assents to her abduction by the “ape man.” That all seemed acceptable; boy meets girl, imperial power meets “dark continent.” The British has a “thing” for the untamed continent. Explorers like Livingston, Burton, Speke, and exploiters like Rhodes, were lured there by the prospect of fame and fortune, or both.

In may respects, the Tarzan movie was an analogue for colonization. Soon enough, Tarzan was speaking English (“Come, Jane, let’s do it again swinging from a vine.”) Tarzan was the “white guy who had ‘gone native,’” but then, after Jane, he was rescuing his fellow whites from surly “natives” (and native beasts) and was enlisted in subduing them as well. Jane’s outside world seductiveness introduced an ambiguity into Tarzan’s allegiances. Hence, Tarzan films had man of the dramaturgical elements tat made colonialism and imperialism interesting to me—the inter-cultural swirl of the intrusion of one culture into another, the way in which race, religion, gender and, always where the British were involved, class, clashed and modified one another. Drama is essentially conflict, and there is abundant conflict in empire building.

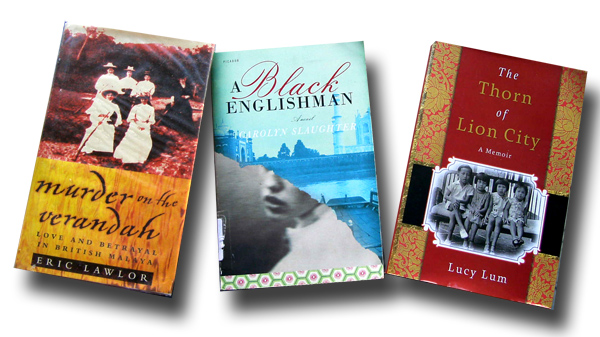

The three selections treated here by no means cover the range literature on the subject. They each deal with the British Empire in South Asia, one semi-autobiographical, another by an American, and the third is memoir by a “local.” Murder on the Verandah, by Dublin-born American writer Eric Lawlor, is subtitled “love and betrayal in British Malaya,” and takes its impetus from a murder by an English woman, wife of a British civil servant, of an associate of her husband’s who might have been her lover, possibly a rapist, that put her on trial that exposes many of the features of British colonialism in Asia in 1911. The author makes the point in the preface that “Two Englishmen, ne her [Malaya] and one at home, might easily be men of different race, language, and religion so different in their outlook and behavior.”

The British seemed to bring pretty much everything of their culture with them. Most declined to learn local languages and eat local foods, they imported their magazines and music, their sports and amusements such as horse racing, keeping much to their circadian schedules and habits, simply reproducing what they had left behind. However, the ad the advantage of doing this with the assistance of servants and other minions which most members of their class would never enjoy at home. We see evidence of these behaviors time and again in the works of E.M. Forster, Paul Scott, Conrad and Orwell, among man others.

The trial and aftermath of Mrs. Proudlock, who killed her fellow countryman with her husband’s revolver serves as a means for the author to explore the various dimensions of colonial life. Thr British seemedto develop a colonial pathology. There was the usual homesickness and boredom that comes from being separated from family and familiar surroundings. Men were often at their jobs away from the settlements (“Malaya was a man’s world”), leaving women on their own for long periods. Drinking and gossip were ways to fill the void, often at clubs established much for those pursuits. In Malaya, at least, there was a lot of what was called neurasthenia (a mental cocktail of lethargy, fatigue, irritability and depression) Malaya had a surprisingly high rate of suicide, twice the rate of self-destruction as in England, Part of this was attributable to business reverses (in Malaya it was rubber plantations), but strains on marriages also played a large part. There was also the constant threat of local diseases, especially malaria. The British didn’t seem to like their servants much, and the feeling was requited. They regarded one another with suspicion and through the lenses of ethic and racial bigotry.

Marital fidelity and race figure prominently in The Black Englishman, Carolyn Slaughter’s novel that is based heavily on the life of her maternal grandmother, whom she only came to know when she returned to England to spend her last years in a mental hospital. This story is in the same time period, but narrated by twenty-three year old Isabel Webb, who seeks adventure and escape from a dreary life in England by marrying a British military office posted to India. Isabel only gets to know Neville intimately on their way out aboard ship. But no sooner are they arrived at the military outpost in Northern India tan Neville decamps for some remote territorial outpost and pretty much and Isabel realizes that he is really married to the British army and is a man set in is routines and prone to violence.

In a military settlement with much gossip, booze and the occasional suicide Isabel survives as she starts to “go native,” something that is frowned upon, as is any unseemly relation between a memsahib and an Indian. Isabel defies most of the colonial conventions, befriending her older man-servant, learning Hindi, and eventually falling in love with and Indian physician. The naïve counterpart of “going native” for Oxford-educated Dr. Singh is to try to become a “black Englishman.” Isabel and Singh are co-adulterers, he having a wife with whom he spends little time. The relationship runs afoul, as these sorts of relationships always seem to do, of the disapproval of them by both ethnic groups. The return of Neville, bent upon violently avenging his being cuckholded, parts the inter-ethnic lovers and Isabel suffers mentally from being alone again.

A quite different perspective comes from the memoir of a young Singaporean-Chinese (called “Straits Chinese) girl. The Thorn of Lion City, by Lucy Lum, covers her childhood years during the late 1930s and early 1940s, a time when Singapore was still a British colony and much the product of Sir Stamford Raffles. Beyond the fact that she incorrectly thought the British would repel the invading Japanese in 1941, Lum does not have much to say about her overlords. What her story provides is a childhood level view of being from and immigrant group within a colonized society. But, being a child, the reality of her life is in the family and, by almost any western standard her’s was a supremely dysfunctional family. To a Brit, Lum’s family might have seemed the perfect justification as to why British civilization was needed in these parts. Being a girl (the third of seven children), Lum was at the low end of that family hierarchy. She is literally tortured by her mother and especially her maternal grandmother, Popo, who beats her for the slightest infraction and once burned her lips with a cigarette for telling (the truth) about her brother. She also inflicted her grandchildren with wretched herbal concoctions and bizarre superstitions.

The British literally pay no role in the life of Lum’s family, which is ruled by the senior women. It might have been a family straight out of southern China in the 19th century. Lum’s rather intellectual father was a linguist who supported the family as a translator. He knew enough Japanese to translate for the Japanese military and probably kept the family safe. For this he was browbeaten and vilified by his wife and her mother, and loved by young Lucy. The day he died his wife took up with another man. She had earlier consented to the giving away of one of her female children.

Also interesting is the prevalence of the muichai practice (called mui tsai, or “little sister,” in Hong Kong Cantonese) as late as the 1940s in Singapore. Muichai were girls who were literally sold, usually by their parent—in effect to become slaves in other households to be worked and exploited in other ways. Grandmother Popo beat and tortured them as well. Self-esteem among Chinese girls in these times was not very high.

These days Singapore is virtually run by Straits Chinese. The British hegemony has been gone since 1965, one of a string of jewels in Victoria’s necklace that has been surrendered along with India and Malaya, now Malaysia. At times the Empire was brutish as well a British. The record is mixed from the point of view of human relations, but the British were, as colonial powers go, far from the worst.

One as to place into this account perhaps the prime residual advantage of the Empire—not the English, but English. From a purely selfish point of view it has relieved me of being forced to acquire fluency in other languages. If maps, menus and street signage, professional journals and other forms of communication from political posters to museum displays are to be found in a non-local language it is likely to be English. English is the lingua franca of airlines, business, science and education—and the Internet. Through English, and educational systems based on it, many former colonies have been better positioned than other countries to participate in the global economy.

And to think, one of the memorable lines from first encounters with English and the English was “Me Tarzan; you Jane.”

___________________________________

©2008, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 1.17.2008)