China’s astounding emergence onto the world stage economically has been largely portrayed through images and accounts of its great cities. It has some 120 cities that are over a million in population and the giants, like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou are approaching 20 million. The “one-child” policy may still be in force, but there are estimated to be some 150 million Chinese migrating towards the cities and the economic opportunities they offer. In those cities are Chinese driving expensive late model automobiles from Germany, Japan and the U.S., soaring commercial buildings and luxurious apartments and condominiums, and fellow citizens wearing clothing worth more that a year’s income of “countryside” people.

China’s astounding emergence onto the world stage economically has been largely portrayed through images and accounts of its great cities. It has some 120 cities that are over a million in population and the giants, like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou are approaching 20 million. The “one-child” policy may still be in force, but there are estimated to be some 150 million Chinese migrating towards the cities and the economic opportunities they offer. In those cities are Chinese driving expensive late model automobiles from Germany, Japan and the U.S., soaring commercial buildings and luxurious apartments and condominiums, and fellow citizens wearing clothing worth more that a year’s income of “countryside” people.

This is the image of the “new” China, the China that will host he 2008 Olympics, the China that official China wants the world to see, admire and respect. This is the China that took Deng Xiao-ping’s permission to embrace capitalism and “get rich,” whose leaders have exchanged those clunky Mao suits for Armani. This is the China that has been admitted to the WTO and has joined the global economy and produces much of its consumer goods

.

But the greater part of China, come 900 million Chinese peasants will not be part of this picture. The “average” Chinese is not a BMW-driver talking on a cell phone to his plant manager or broker; he/she is a peasant farmer heading out into the fields to scrape out a subsistence living. And rather than having party cadres a willing partners in their enterprises, they are most likely to have them as the burdensome exploiters who will forever keep them destitute.

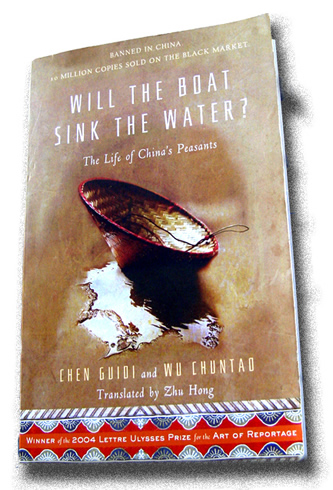

Reading Chen and Wu’s book will have you wondering why the whole 900 million of them don’t pack a bag and head for one of those prosperous metropoles in the “special economic zones.” That might be the reason that their book was both banned in China and selected as the winner of the 2004 Lettre Ulysses Prize for the Art of Reportage.

Chen and Wu concentrate on the fate of peasant farmers in Anhui province, along the eastern stretches of the Yangtse. Nearly 65 million people live there, at about 1,200 to the square mile. Their style of reporting is narrative. They are the poignant stories no peasant farmers and villagers who are exploited by low-level government officials ad party members in ways that might make the detested “landlords” that dominated the peasants prior to the revolution seem like kindly benefactors.

Anyone who has seen The Good Earth, or read Pearl Buck’s book, knows that aagriculture has long been a difficult profession in China, subject to such disasters as floods, droughts and plagues of locusts, as well as the exactions of rapacious landlords. But agriculture has also been one of the great disasters of the Chinese centrally controlled economy. Collectivization resulted in enormous declines in productivity from its very beginning in 1956. It was forced upon the peasants and many revolted and were labeled “rightists. By 1958 the Great leap Forward was underway that consolidated the collectives into communes and the peasants lost all their property and belongings. This communization gave everything to the state. It was a disaster and, starving millions. In 1966 began the decade long Cultural Revolution, during which a peasant could be accused of taking the “capitalist road” if his household kept two chickens or panted a few vegetables for the market. Productivity dropped so low that the a value of ne day’s agricultural labor averaged a mere 11 cents—the equivalent value of a day’s labor in the Han Dynasty, two thousand years ago.

Flailing around for something that would both produce food and revenue for the government the commune system was converted in the 1980sn into sixty-thousand administrative “townships” invested with the power to impose and collect taxes. While productivity increased the new system served to create a huge bureaucracy of party operatives at the township level that not only siphons off any “profit” many of the peasants might realize, but which also has to be paid for by the peasants. The bureaucracy acts like a plague of locusts.

The principal mechanisms are the taxes, fees and exactions that would drive an American anti-taxer to distraction. Township authorities may impose “fund-raising” taxes for building township office buildings, schools, clinics, broadcasting stations, theaters, and several vague enterprises. The peasants must also pay up for village cadre’s allowances and business trips, the Party Youth League, and Townships People’s Congresses, salaries for Village personnel from the Party Secretary to the plumber, all school expenses, all birth-control programs, and a large number of social programs. While some of these can be considered legitimate expenses for operating a government, the bureaus don’t stop there. For example, Chen and Wu came across the following situation for getting married in one township. “The happy couple has to pay for the marriage certificate. [But] Then there are fees for the letter of authorization (provided by the work unit or the village committee, certifying the identity band age of the applicants); the notary; the prenuptial physical (presumably checking for infectious disease), and a fee for a comprehensive physical for the bride. After these preliminaries, there is a deposit for commitment to the one-child policy, a deposit for commitment to family planning, a deposit for commitment to deferred pregnancy. After the birth-control part is taken care of, there is a deposit for commitment to ‘mutual devotion,’ and a deposit for a ‘golden wedding.’ Apart from these deposits, there is a tax for the wedding banquet, a tax for pig killing, a ‘green’ tax for banquet-related environmental hazards, and finally a donation to the Happy Children’s Center.’

A lot of these funds end up in the pockets of local cadres ads evidenced by the cars they drive and the homes in which they live. They get away with a lot of these “extortions” because the can operate like a local MAFIA in the way they enforce their “collections.” Thugs are often brought in, or the complicity of the local cops, to rough people up and, if they can’t or won’t pay up, take their crops, livestock, even personal possessions from their homes such as furniture and appliances. The reporters document cases of peasants being crippled and even killed. Complaining to other local authorities can result in a visit from the thugs, beatings, or a stay in jail. The journalists report on the fates of some peasants who went to Beijing to complain and ended up tortured and imprisoned when they got back.

Not all local officials are this corrupt, but the system seems an ideal matrix for this sort of taxing the peasants to a point where they remain at not much more than a subsistence level. While the growth rate of then cities and the industrial economy has grown by leaps and bounds, the agricultural sector lags far behind. The central government is not unaware of the monster they have created, but one that also kicks a lot of cash into its coffers. There have been arrests and demotions of local officials, protest by the peasants (although not much of this makes the news.) But the culture of corruption runs deep in not just the agricultural sector of China, deep enough that if, someday, the boat does indeed “sink the water,” the bottom is going to turn out to be a long way down.

____________________________________________________________

©2008, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 5.31.2008)