a review of Revolutionary Road and the Cinema of Suburbia

Our property seems to me the most beautiful in the world. It is so close to Babylon that we enjoy all the advantages of the city, and yet when we come home we are away from all the heat and dust. [Letter written in 539 B.C.]

Our property seems to me the most beautiful in the world. It is so close to Babylon that we enjoy all the advantages of the city, and yet when we come home we are away from all the heat and dust. [Letter written in 539 B.C.]

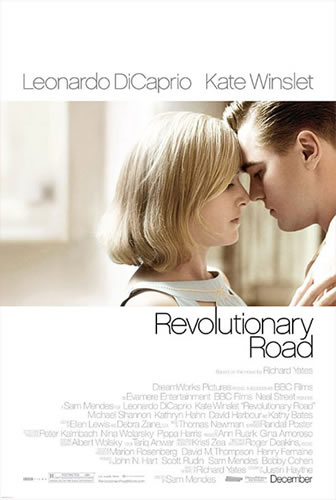

2547 years later comes the release of Revolutionary Road, in the midst of a global economic recession ignited by a housing crisis fueled by “sub-prime” housing mortgages, comes another tragic suburban drama. Set in the early 1950s, when the “suburban dream” was just taking form, the Wheelers, Frank (Leonardo DiCaprio) and April (Kate Winslet) and their two young children abide in a classic clapboard “Early American” suburban home on a very generous grassy plot. They are a demographic cliché; Frank commutes to the city by train to a boring corporate office job, April is what we now call a “stay-at-home mom.” They are like many other couples forsaking the city to set up a life “away from all the heat and dust.”

There is not much of a story in that, but in Richard Yates’ novel on which this Sam Mendes film is based, the Wheelers are sufficiently introspective and projective to discern that their suburban dream just might be existential death. Frank’s job is unfulfilling with the same co-workers, the same lunches, an occasional dalliance with a secretary to relieve the boredom. An acting role in community theater only depresses April. So why not Paris, the ultimate city of expat dreams in the 1950s? Frank had been in Paris during the war, and the suggestion to April that they might chuck it all and live an exciting urban life.

No sooner are their plans to escape suburbia announced to their friends and Frank’s co-workers than realities intrude. April learns she is pregnant and Frank objects to her wish to have an abortion, but maybe he is really lured by a promotion in a company that appears to have a future in the digital revolution. The existential reality of the suburban life they have already made is torn raw in a visit by a neighbor’s mentally deranged son whose verbal rages contain truths the Wheelers seem unable speak to one another. Their suburban dream turns into a prison of mutual contempt until April tragically botches her self-administered abortion.

Surely, there have been couples that have come to grief in Newark, Detroit, Indianapolis, and other cities. But suburbs have for millennia been places with more quietude, space, cleaner air and greenery, especially grass, where families could be raised away from urban traffic, housing density and the proximity of the motley throng of immigrants. They were the ideal vision of the best of city and country, the antidote to the pressures and discomforts of urban life.

In fact, American suburbs have performed a far more practical function: they did not just allow erstwhile urbanites access to the countryside, but they allowed them access to the middle class. The lower land prices of exurbia permitted millions of former apartment renters in the city that had gained no interest or equity in property to take acquire the most essential aspect of the “American Dream”—home ownership. The home, a steady job, and a car to commute to it became the three-legged stool on which that dream rested. But for some, it could all go up in barbeque smoke. For some they dare not allow themselves the question, “is this all there is?”

For most suburbia was an economic foothold; for many the reality was close enough to the dream. But, since the cinema is interested in drama, not satisfaction and complacency, it was misfits and miscreants that drew its attention. Hexemplified by films such as Please Don’t Eat the Daisies (1961). Based on a best-selling humor book about the suburbs it was also a vehicle for Doris Day to showcase a hit song of the same title. Day and her screen husband (David Niven) move to the suburbs at her insistence, but he must continue to work in New York, where he is a drama critic and there is the temptation of city women (Janis Paige). Minor misunderstandings, and other plot elements that soon became the staple of television sit-coms, resulted in ultimately happy endings.

These kinds of comedy situations pop up again in suburban settings in Wives and Lovers(1963), and The Grass is Greener over the Septic Tank (1978). By far the most amusing scene on this theme appears in The Prisoner of Second Avenue (1975) where urbanite Mel Edison (Jack Lemmon) is having a nervous breakdown because he has lost his job. He and his wife, Edna (Anne Bancroft), are invited to the suburban home of his older brother, Harry (Gene Saks). No sooner do they arrive and are accosted by Harry’s enormous dogs than Harry begins extolling the advantages of the suburbs over the city. He badgers his brother to fill his lungs with the fresh air, and to walk over his extensive property, from which Mel gets poison ivy. Meanwhile, Harry’s wife involves Edna in her home-making projects and gardening with comic ineptitude. The city dwellers seem relieved to return to their high-rise apartment and be free of the sub urban zealotry of their well-meaning relatives.

With the exception of The Prisoner of Second Avenue, such conditions hardly qualify for a compelling comedic or dramatic setting, unless the security and serenity of suburbia are threatened by circumstances alien to its putative homogeny and conformity. Indeed, this dramatic plotline appears to be a common one when screenwriters elect to address life in the suburbs.

That a film might be titled Bachelor in Paradise (1961) is an indication that the suburbs were family-centered places in which an unmarried individual would be a sufficient anomaly to drive a plot. The suburb in this case is a generic California subdivision of new homes inhabited mostly by young families in a circadian round of husbands departing en masse to jobs in the city, and wives engaged in child-rearing, homemaking and coffee-klatching. One establishment shot shows an early morning routine in which all of the husbands on a street depart at the same time in cars backing out from garages and driveways and driving off on the commute to the city.

Introduced into this paradise is a womanizing best-selling author of books observing the manners and mores (particularly romantic) of Europeans. A.J. Niles (Bob Hope), compelled to spend a year in the U.S. for tax purposes, decides to use the time writing about American suburbanites. As a bachelor who is the sole male remaining in the subdivision with a potential harem of somewhat bored wives, Niles becomes the subject of amorous possibility for some of them, and a threat to their husbands.

Much of Bachelor in Paradise is a stage for comedian Bob Hope deliver one-liners, and for situation comedy sequences. Along the way much fun is poked at suburban lifestyle and the need for something interesting to happen in it. As it happens, the other single individual in the cast is Rosemary Howard (Lana Turner), the woman from whom Niles is renting his suburban home, and there is little doubt they will end up together. Anyone who settled in a California suburb in the 1950s or 1960s will immediately recognize the setting of this movie, and perhaps the social ennui as well.

Marital infidelity was only hinted at in Bachelor in Paradise. But that was before the “sexual revolution.” By the late 1960s and the 1970s the suburbs were a couple of decades old and sexual escapades had come to be regarded as a prime preoccupation to relieve marital boredom. The Ice Storm (1997) looks back to the 1970s from the vantage of some thirty years on. The suburb is New Canaan, Connecticut, the hometown of the Hood family. The “new way of life” has already begun to tatter, and nice houses, late model cars, and good schools, are no guarantee for happiness in suburbia. The father, Ben Hood (Kevin Kline) is having an affair with the mother of his children’s friends. Ben’s wife (Joan Allen) suspects it and has retreated into her own emotional “ice storm.” Their children, Wendy (who plays sex games with the boys next door) and Paul, are at least, if not more, grown up as their parents (whom they refer to in their private language as “parental units”).

During an actual ice storm, which glazes the suburb, the adults engage in games of wife-swapping that were becoming popular in the period. At boozy parties men threw their car keys into a bowl and women chose randomly from it to determine their sexual partner for the night. But as director Ang Lee looks back upon this recreation from the vantage of later years the scene takes on an irony. The men evidence an anxiety over having their keys drawn from the bowl, and one woman is relived that she has selected her own husband’s keys. Supposedly even the swinging lifestyle of suburbia quickly loses its momentum.*

It is bored suburban husbands, preoccupied with crabgrass and spying on each other, who drive the storyline of The Burbs (1989). With little else of interest, the writers reprise the plot from Frankenstein: mysterious, unsociable, and unsavory looking neighbors move into a dilapidated house next door to the family of Ray Peterson (Tom Hanks). Ray, concerned about his property values, but also suspicious of strange noises and lights coming from the shuttered old house, is fed sinister scenarios by other bored husbands. A neighbor who has not been seen for days is considered to be a victim of some vile doings. After a social intrusion (under the ruse of being “neighborly”) the newcomers prove to be absurdly sinister looking and have strange accents.

In search of evidence of evil-doing, Ray and his fellow protectors of the neighborhood break into their house while the occupants are away. After several silly mishaps, a gas main in the basement is broken and the house explodes. When the occupants return they are exposed as ghouls after the trunk of their car is shown to be full of human bones. The Burbs has little, if any, cinematic or sociological value, although it is interesting that its writers seem to take delight in having the youth of the subdivision act as observer-narrators who’s main enjoyment of suburban life was watching their parents make fools of themselves.

A more interesting variation on what might be regarded “the Frankenstein in suburbia” sub genre, involves a young man created by a weird inventor, again in an old gothic mansion at the edge of s suburban subdivision. With allusion to Pinocchio as well, a lonely aging inventor turns a cookie-cutting machine into a young boy, but dies before finishing the project, leaving the boy with scissors for hands. Edward Scissorhands (1990) is an endearing little Frankenstein, played touchingly by Johnny Depp. Reclusive Edward, who knows the outside world only from the magazine pictures he has clipped, is discovered by Avon Lady Peg (Diane Weist). She brings Edward to her home in the pastel-painted suburban tract and introduces him to her husband, Bill (Alan Arkin), their son, and cheerleader daughter, Kim (Wynona Ryder). Edward’s pasty complexion is often scarred when he attempts to flick away his long unruly hairs. He wears a Goth-inspired black leather suit, which only adds to his alien stature. Much is made of Edward’s physical predicament; he not only scars himself, but puncture waterbeds. But he also is capable of giving haircuts, and creating, with great artistic flurry, topiary and ice sculptures.

Director Tim Burton also shows how the curiosity of some of the suburbanites about Edward turns suspicious and hostile when Edward is called a fake and a freak, and is bullied toward crime by one of the local boys. Even an oversexed housewife tries to seduce him. In the end, suburbia is too unaccommodating for such a misfit and Edward is once again alone. Like ET, Steven Spielberg’s cuddly little alien visitor to another American suburb, he really doesn’t quite fit in when the initial curiosity wears off because its normalcy and security that suburbia wants most.

According to Hollywood, the last thing any property-value respecting suburbanite wants are “neighbors from hell.” Neighbors (1981) presents Dan Ackroyd and John Belushi playing against type in a farce about middle-class suburbanites. Earl Keese (Belushi) is a polite and nervous man living and uneventful life with his unremarkable wife when macho, boisterous and boorish Vic (Ackroyd) and his vixen wife move in next door. The movie proceeds as a send up of suburban conventions and expectations about to descend into a suburban nightmare. Wife-swapping is the theme in another suburban neighbors film, Consenting Adults (1992), in which Kevin Spacey plays the threatening neighbor who broaches the subject to his benign and retiring neighbor played by Kevin Kline. But the ultimate suburban neighbor from hell might be “the terrorist next door” played by Tim Robbins in the innocently titled Arlington Road (1999). While essentially a thriller that takes its market impetus from the events of Oklahoma City, it’s suburban setting lends an especially unsettling element to the possibility that the person mowing the next door lawn or firing up the barbeque might have as benign an appearance making a sinister intent as that of Timothy McVeigh.

We have witnessed the wholesomeness that characterized the early films set in suburbia give way to satire and then to darker themes. The sociological fact was that suburbia changed the environment, but it didn’t really change people. The American tendency to put too much faith in physical determinism, much in the same way we regard our nation and it’s ideals as historically exceptional, proved to be unfounded. If suburbia was the best expression of the American Dream, it was found wanting. Suburbia’s critics made the same mistake, stereotyping suburbs as homogenous social wastelands concerned with crabgrass and keeping up with the Joneses. Demographically, suburbs were often more ethnically diverse than inner city ethnic enclaves.

Although suburbia became associated with the American Dream it was also often purchased at the expense of other aspects of the American experience. This is an aspect of the subject that rarely makes its way into cinematic expression, except indirectly. Chinatown (1974) is a film noir murder mystery, but it is set in Los Angeles in 1937 during a drought. This was also the period in which the city was expanding into the San Fernando Valley. The film chronicles the chicanery of corrupt public officials and land speculators behind the construction of a reservoir and the eventual building of new suburban housing developments. Los Angeles had already proved itself to be a place where the “gold in the hills” was real estate value. Between 1906 and 1926 it went from twenty-nine square miles to over four-hundred square miles. In the arid climate of the Los Angeles basin it was water that made that grew real estate value and the political power that came from an expanding city.

Corrupt politics aside, the suburbs ate up erstwhile farmland, swallowed small towns, and eventually established political rivalries with central cities. As suburbs matured internal political divisions emerged as well, tax burdens increased as new services were added, debates over growth, integration, pollution, and other matters began to remind some of the problems they had supposedly escaped the city to avoid. Central to many of the problems of suburbia was the question of property values.

While suburbs were associated with familism, they also engendered a growing independence for women, who took more responsibility for the development of the social infrastructure of these areas, sitting on school boards, establishing Girls Scouts and Little Leagues, selling real estate, and other activities. This independence took flower among some suburban women in the 1960s and 1970s in the “women’s movement” and also posed a threat to the notion of suburban family solidarity as more women questioned traditional marriage roles and marriage itself.

By the close of the millennium the suburbs had become such a dominant feature of the American urban scene that films set in suburbia no longer had much of a locational distinction. The largest demographic cohort going to the movies now comes from the suburbs, filing into the multiplexes in suburban malls to see films that may well be made by film makers who, like themselves, were born and raised in suburbs. Films such as Welcome to the Dollhouse(1995), about an awkward and unattractive girl in a suburban high school humiliated by her classmates and unsatisfied with her family, or the schemes and infidelities of Election (1999), or The Ice Storm (1997), all plumb the sinister, dark, and unfulfilling sides of the suburban experience.

Moreover the line between city and suburban is less distinct. Suburbs increasingly are experiencing many of the problems associated with the inner city. Americans are less shocked to learn of school shooting like those at Columbine and other sub urban schools, perpetrated by students with all the supposed material advantages of suburbia. The scourge of the triangle of drugs, gangs and prostitution, once associated exclusively with inner cities, has surprisingly made its way into the American suburb.**

When American Beauty (1999) received the Academy Award for best picture in 2000, the suburbs might have seemed to have finally arrived as environments that could be taken seriously for cinematic drama. That is, the suburbs were no longer those tracts of bungalows and Cape Cods of the 1950s portrayed in farces like Bachelor in Paradise. Nearly a half-century of American suburbanization has brought us to the realization that it is not so much where we are, but what we are, that makes the difference. Urban planners, who long denigrated and scorned the visual blandness of suburbia, continue to offer physical fixes and palliatives. “Neo-traditional” design proffers communities that harken back to the neighborhoods and small towns before the suburban era, places where, presumably, people sit on stoops and front porches, greeting neighbors, and women push prams along cozy streets of American Gothic homes. But “neo-traditional” design cannot make neo-traditional people, families, jobs, and values.

American Beauty is, in a sense, a summation of suburbia’s social pathology set against an antiseptic physical environment. With beautiful colonial homes set in manicured lawns, driveways full of late model sports utility vehicles, all the surface features of the American Dream are all present in the establishing shots. But the narration track tells a different story. Very much is wrong with Lester Burnham (Kevin Spacey), his family, and his neighbors. Entrapped in a mid-life crisis, masturbation is the highlight of his day. He has a beautiful, but “Stepford,”*** wife, and a sullen daughter who regards him as a loser. The viewer tends to identify with Lester because it is his story and he is its narrator, with all the grim irony of Joe Gillis in Sunset Boulevard. Lester hates his job so much that he is willing to resign from it and take a burger-flipping fast food, minimum wage job instead. His wife is unfaithful to him and he has an infatuation with a high school cheerleader. He may be flailing about, but at least he is rebelling. None of it turns out satisfying for Lester, not the house, not the job, the family, or the neighbors. American Beauty even reaches back to the old suburban them of the neighbors from hell, in this case, a Nazi memorabilia-collecting homophile ex-Marine and his weird voyeuristic son.

Perhaps it is because America never seemed to have enjoyed a golden urban age that the suburban dream seemed to offer so much promise. Americans have always had a good case of anti-urbanism. They might have left the farms and small towns in great numbers to take advantage of the allure of the city and its riches, but they seem to have done so without fully grasping what that meant in terms of the diversity, disorder and distance from traditional norms, and they have retained a nostalgia for those “good old days” that never were, but fade into myth with the passage of time. Suburbia was the compromise. It did deliver much of the material promise of the American Dream. Many Americans entered the middle class through the door of suburbia. But in both the virtual and actual suburbia on the other side of that door is a volatile world on the edge of self-destruction.

That the first Academy Award “Best Picture” of the new millennium was American Beautymight have seemed to express Hollywood’s summary dark vision of a suburban future centered on the theme of contemporary American suburban disappointment. It is perhaps significant that “suburbia,” the most significant American urban phenomenon of the latter half of the 20th century, was the kick-off theme for the next century. By going back to the 1950’s to examine the genesis of that disappointment in Revolutionary Road, Hollywood apparently feels there is more suburban angst mostly suburban moviegoers are willing to pay to see. It is not just the superb screenwriting and acting that make films like American Beauty and Revolutionary Road such a successful films; it might also be its plausibility.

____________________________________________________________

© 2009, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 7.4.2009)

*Apparently not with everyone, however. The 1999 documentary, The Lifestyle, chronicles the activities of those who have adopted swapping houses and spouses as a full-fledged way of life. Spoken of by its adherents with almost religious zeal, the “lifestyle” is promoted as something that can even, paradoxically, enhance marital fidelity and monogamy. The documentary shows them to be rather dull, and unappealing people, who sometimes admit they have not found sexual paradise and opt out for more conventional lifestyles. It is also notable that what came to be called “swinging” (partner swapping) in the 1970s also proved to be, if in perverse form, an expression of the growing independence of women in American society.

**From Rubies to Blossoms: A Portrait of American Girlhood: The New Gangs of New York, National Public Radio, February 8 – 9, 3003

***She, like Rosemary (Lana Turner) in Bachelor in Paradise, sells real estate.