Several years ago I was on a bus traveling through the West Bank of Palestine. As we passed through the ancient city of Hebron, a holy place to both Muslims and Jews because it contains the burial place of Abraham, the father of both religions, I could not help but notice the bright new residential constructions on the hills surrounding the old city—Israeli settlements.* Other than the hegemony of Jerusalem there is perhaps no more contentious issue that keeps Palestinians and Israelis at one another’s throats—and by extension, American and the Muslim world—than the building of Israeli settlements in erstwhile (pre-1967 war) Palestinian territory. In President Obama’s address to the Muslim world in Cairo on June 4, 2009, he stated unequivocally that the process of Israeli settlements (the settlement of lands conquered in war is also proscribed by the Fourth Geneva Convention) must cease.

Several years ago I was on a bus traveling through the West Bank of Palestine. As we passed through the ancient city of Hebron, a holy place to both Muslims and Jews because it contains the burial place of Abraham, the father of both religions, I could not help but notice the bright new residential constructions on the hills surrounding the old city—Israeli settlements.* Other than the hegemony of Jerusalem there is perhaps no more contentious issue that keeps Palestinians and Israelis at one another’s throats—and by extension, American and the Muslim world—than the building of Israeli settlements in erstwhile (pre-1967 war) Palestinian territory. In President Obama’s address to the Muslim world in Cairo on June 4, 2009, he stated unequivocally that the process of Israeli settlements (the settlement of lands conquered in war is also proscribed by the Fourth Geneva Convention) must cease.

One of my favorite topics back in the days when I taught my Seminar in Urban Theory was titled “Space and Place.” Anyone who has read these pages with any regularity over the years can see that I haven’t “let go” of my interest and fascination with the way in which humans relate to terrestrial space.** Space is, of course, just that, space—volume of some dimension or another, ad variously “contained.” We fill various volumes of pace with different things—packing our suitcase space, or closets with things, leaving parts of other spaces unfilled, and even putting entire cities and countries in space, and, of course, floating around in space on our little planet.

But space gets filled up with something else—with human experience. It is our human experience in space that fundamentally changes a discreet part of space into something else, something that is not created by the Big Bang, or God if you wish, but by us. Space becomesPlace. A place differs from space in that it is where something happened. That is why humans mark, and remember, and often care deeply about places—because something happened in a place.

What actually happens in a space might not be of especially great social-historical moment. It might be the place where you were born, or where some other significant aspect of your lifetook place. It might be the place where you met the love of your life. It might just be your old neighborhood. But it will be a place with a significance unique to you. When we return to such a place, say, after many years away from it, our memory and the actuality of it merge—often with distorted scale and clarity—the two lenses on the same object might be out of focus.

Moreover, we can see in this conceptualization that place is not only about where (Space), but also about when (Time)—hence, this is where I was when something happened. Places are therefore our nexus of space and time; they are our aides de memoire that situate us in bothplace and memory. This is why they are important to us, because they (re)locate us in the stream of our lives. People who are driven or otherwise removed from their place are dis–placedpersons.

But there is another dimension to the importance of place in human existence; that is where there is a significance of place in a collective consciousness. What as happened in various places can acquire significance beyond personal experience that bestows up such places great power and importance through which a virtual or vicarious “experience” is conjoined. The mere evocation of Rome, Hollywood, Paris, Nashville, Benares, Mecca, Shanghai, Jerusalem, or specific points or locations within them evokes meanings and emotions of historical, political, religious, artistic or other importance, even for people who have never encountered such places beyond media or imagination. Numberless other places, Omaha Beach, El Alamein, Wounded Knee, Dealey Plaza, Yalta, Bikini Atoll, The Vatican, The Killing Fields, Versailles, Auschwitz, as randomly chosen from memory, all evoke common recognition and emotions.

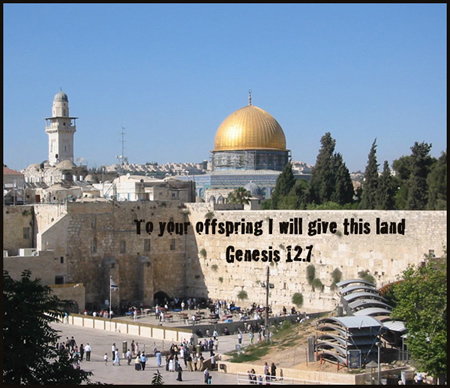

This is where we return to the matter of the hegemony of such places, especially contested places such as Jerusalem, or Hebron. Israel’s right-wing parties have offered rationale for settlements as a necessity for “natural growth,” a term that bears an uncomfortable ring of Germany’s lebensraum. But also to be heard are that the lands of Palestine’s West Bank are “holy,” bestowed in ancient covenant by God to the people of Israel. Such claims are hardly unique to the Israelis. In the historical scrambling and rearrangements of territories (especially in the Middle East) from Balkans, to East Timor, on every continent, aboriginal presence, rights of first arrival, and particularly religion have been and are the source of disputes and conflicts over discreet chunks of he surface of the earth.

While peoples might share common biology, similar histories, and even share similar governmental principles, the sharing of space tends to emphasize differences. The Western Wall and the mosque on Temple Mount in Jerusalem, for example, occupy the same location—but a different elevations—and each represents a major religious/historical event for two different faiths. Both spaces and places are territorially mutually exclusive; that is, each space and place is discreet and territorially mutually exclusive. I, for example, am writing this at a café that is at 32 degrees, 44’47 minutes and 18” seconds North, by 117 degrees, 10’32 minutes and 98” seconds W on the face of the earth. No other space or place shares or has those coordinates. Place is finite and defined by arbitrary borders; when I occupy this able, this is exclusively, if only temporarily, my place.

Humans, being place-makers (other animals attempt to control territory, but so far as we know, not for symbolic purposes), being inclined by fear to religious beliefs, and land being finite and never purely substitutable, seem destined to conflict. For our relatively brief existence there has failed to develop an ethos capable of resolving the disputes over space and place. As creatures of memory, humans are by nature, place-makers, but since space is finite, it is only religion that is variable in this equation. Unfortunately, as each human cohort has chosen its supreme god, each feels justified in claiming that their god has bequeathed them their “promised land.”

____________________________________________________________

© 2009, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 6.8.2009)

* See DCJArchives: 19. 5: Sweet Waters in the Promised Land (Part 2) 4.13.2005.

** See, for example, DCJ Archives: 4. 3: The Home of the Gods 1.07.2004; 4.7: . . . and they shall be led into the land of corn (1.12.2004); 4.3 The Home of the Gods, 1.7.2004; 25. 5: The Planners are Coming, The Planners Are Coming!! 10.17.2005; 43. 2: The Pig in the Parlor 10.7.2007; 24. 6: The Blancocruxians 9.16.2005.