A NOTE TO THE READER: This short story is adapted from my book in progress, The River Dragon’s Daughters, a story based on female infanticide and the Three Gorges Dam ion the Yangtze River in China. The red line represents the height the water will rise behind the dam above the current river level, inundating many towns and villages and necessitating relocations of millions. It is based partly on two of my visits to Sichuan. (J. Clapp)

© Pauline Shu, 2001

Below the red line. Above the red line. The red line cleaved Sichuan’s fate. It’s like the dirt ring around a bathtub, Nick Hanna thought. They’ll fill the Sichuan tub up to the ring. It’ll be the world’s biggest bathtub, but the plug will never be pulled on this one. Maybe.

Right about now Hanna would like a nice bath, a couple of hours into trudging along the narrow path etched into the side of the gorge-steep slope that rises from the fast-flowing sepia river below. Tired and sweaty after making his way up the path that led from that little cove where he stopped to eat his lunch and cool his hot feet in the quiet shallows. Curious little green-brown striped eels, like the ones he’d seen squirming in tubs in the open markets, had slithered up to inspect his toes.

Close by the opposite bank a river cruiser took advantage of the faster current on that side of the river. All Yangtze river cruisers seemed to be painted in the color that Hanna came to call “jade foam green,” a pistachio-hue that was ubiquitous in China. It covered the sides of the Chinese cruise ship (streaked with ochre rust), the decks, the bulkheads, cabins, salons and companionways. On his one and only trip on a cruiser he remembered its hue was modified only by the varying thicknesses of the grimy layer of diesel grease that coated everything. The petroleum flavor was part of a fragrant stew of cigarette smoke, mildew, clogged toilets, galley odors, and a toxic smelling cleaning fluid that all but guaranteed the addition of the acrid smell of vomit.

Now, sitting at the cove, with only curious little eels for company, Hanna felt lonely again. He wondered if the river, which for so long had its way, might soon be brought to human control by the massive dam being completed miles down river. The Yangtze’s currents had shaped, determined, and even taken, the lives of so many for generations that receded into a misty unrecorded past. Soon it might be reduced, at least a great stretch of it, to an enormous deep, placid lake. And under it would repose hundreds of towns and villages, temples and tombs, and the very cove in which he was cooling his feet. The surface, on which oceangoing freighters would be sailing, and calling at new towns along its elevated banks, would be far above where he was sitting, well up the mountainside, up to the red line.

As he made his way up the path to a height nearly one-hundred meters above the cove Hanna figured that he was still below the red line. The farmers and villagers who lived in this area would have to be re-settled in one of the new towns that were being prepared for them. What it would be like for someone whose generations of ancestors farmed these slopes to be relocated to some sterile town and have to find a new livelihood.

That was the reason Hanna was here. Two years ago, back in San Diego, he heard David Chen, a civil engineer born in Chongqing, speak about the Yangtze dam project on the local public radio program, explaining how hundreds of towns, villages and historic sites, even large cities, would sink below the lake that would rise behind the world’s largest dam—the Three Gorges Dam. Since then Hanna had applied for and received a sabbatical and a research grant and the appropriate PRC bureaucrats had signed off so that his host institution would be Chongqing University.

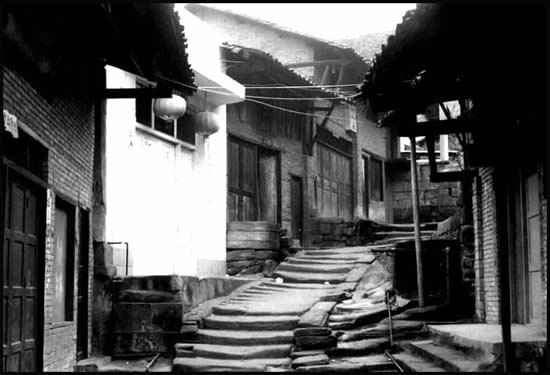

In the four months since he had been in China Hanna hiked all over the red line in the territory between Chongqing and Yichang. The experience had somewhat scrambled his preconceptions and categories. He was a specialist in policies for deliberate, planned urban development, but he had become enchanted with the older, organic and unplanned Chinese towns that seemingly has “grown” and fitted themselves into the Sichuan landscape. Their predominantly wooden structures, the narrow, cobbled, streets of little shops below cramped flats, and the way the towns conformed themselves to, rather than altered, the topography, stood in stark contrast to the post-revolution urban monstrosities of ugly grey slabs rudely rammed into the landscape. It gave him pause when he thought what might be erected to “replace” the old towns and villages that would soon become a vast Chinese “Atlantis.” These old towns were dirty and beaten down, sometimes becoming firetraps or occasionally wiped away in floods, but they were also fascinating indigenous places. With their streets, squares, temples, and buildings reflecting the residue of generations of use, the urban quirks and idiosyncrasies that expressed the personalities of their residents in numberless diverse ways, they had traits that could never be anticipated, or replicated, if even imagined by urban planners. The new cities that would be built to house those from below the red line would never, not for centuries at least, if ever, approach the special urbanity of these doomed, indigenous, old towns.

© Pauline Shu, 2001

In the early morning the village was still damp and shrouded in mist. A hunched and gnarled old woman laboriously pushed a cart, and a man opening the shuttered entrance of his noodle shop, as the crudely rendered sign of a steaming bowl of noodles hinted, were the only people in sight. Hanna could have been in the China of a hundred years ago, perhaps a thousand years. The only clear sign of the present he could discern was the red line that ran across the buildings of one lateral street like the Hebrew houses in the Biblical story of the “Passover.” Except at the Passover the houses with blood on their doors indicated which first-born sons were to be saved; that would not be the case with these homes. The line rudely slashed across the lintels on the front of a small temple and its adjoining meeting house, like a slapped smear of lipstick on a woman’s face, Hanna thought. Then with the suddenness that the sharp demarcation these villages had with the countryside Hanna was on the path through the fields and orchards. Sometimes, where there were no buildings, the authorities would place a small billboard on the slope with a red line on it and the meters above the current river level. He could see one all the way across the river, a white square in the green hillside, but too far away to read.

Outside the village a slight bend in the path that paralleled the river a narrower path intersected from up the slope. Some small vegetable patches of tomatoes, long Chinese beans, and a striped melon or squash looked well tended. He could just see the eaves of a sloped slate roof up above. Wondering whether the structure might have a red line he pushed his weary legs up the path. As he approached the house that was another thirty meters or so up the slope he first heard women’s voices and then saw two figures seated on a cement platform that served as a porch. Hanna was more surprised than the women. They glanced up from their tasks, but didn’t seem at all startled or fearful at the unannounced arrival of a large Western man.

“Nihao,” Hanna called in as friendly a tone as he could muster. It came out as something of a croak; it was the first word he has spoken since early morning when he “nihao-ed” the old lady back in the village. She hadn’t returned his salutation, but this elderly lady did.

“Nihao,” she replied evenly, lifting her eyes to him only as she said it. Her hair, cut in that bowl-shaped Chinese coif called a wa wa tou that is usually seen on young girls, was evenly black and grey. She was squatted on a small, low stool, legs akimbo, washing red and green tomatoes in a wooden tub. As he took a few steps closer Hanna guessed that she was probably older than she looked, maybe into her eighties. He had that surge of inadequacy that had plagued him since he arrived: what does one say after “nihao” when that’s pretty much the extent of one’s vocabulary. Would she continue with a broadside of sentences in the local dialect? But she just went back to her tomatoes. He could have said, somewhat redundantly, “Ni chifanle ma?” “Have you eaten yet?” But in the circumstance it sounded to him like he was inviting himself to lunch.

The girl sat on a low rattan chair, behind and to the side of the old woman and could not have been a greater contrast. She was preparing those long Chinese string beans. But what struck Hanna was the grace with which she was doing it. She was wearing a flower print shift, pulled up just above her knees, which exposed thin limbs demurely crossed at the ankles. Her arms formed and ellipse such that her pose seemed almost balletic. She leaned forward, her back straight, her head slightly cocked. She seemed to take scant notice of the stranger.

Hanna very much wanted a picture of this little tableau. He extracted his digital camera from his backpack and lifted it, pointing to it with his other hand. Qing? But there was no way he’d get beyond “please,” so he just gestured and added, in English: “Please, would you mind if I took a photo of you both?” He said it slowly and with an exaggerated plaintive tone in his voice.

The old woman looked up impassively, and Hanna was preparing to be refused. But she nodded her head in the affirmative, and broke a slight smile.

“Xie, xie,” he said, quickly kneeling and setting the exposure. Neither of them ceased with what they were doing, but Hanna could see in the screen that the young girl almost imperceptibly straightened up and lifted her face slightly towards the camera.

Hanna rose, smiled and thanked them in Chinese again, bowing as he did. Then he started to move off in the uphill direction.

“Will that picture be on the cover of Time, or Newsweek?”

Hanna stopped in his tracks. The voice was almost without accent.

“What?” he said as he turned.

“You’ll need a model’s release if you plan to use that for commercial purposes.” It was the old woman speaking. He could scarcely believe his ears.

“You speak . . .”

“Yes, and a little Italian, as well.”

The girl said nothing, but she had a little smile on her face.

“What a pleasant surprise,” Hanna said. Then thinking that he might be giving insult to the Chinese language, added, “I mean I haven’t had much of a chance to speak English for some time. I’m trying to learn some Putonghua.”

“Of course,” the old woman interjected. “My granddaughter was about to boil some water for tea. Perhaps you will join us? You have learned to drink green tea, haven’t you, because I have no coffee I’m sorry to say. I would love an espresso macchiato.”

“It will be a pleasure.”

Inside Hanna scanned the modest room. There were the ubiquitous framed calligraphic Chinese characters on the walls, along with what appeared to be an intarsia view of the Three Gorges. On the wall opposite where he sat on a divan day bed Hanna could also make out that there were framed diplomas. He could not discern their origin, but he could determine that the lettering was in English, not Chinese.

Over tea Hanna answered questions about his research. There was no need for him to simplify his vocabulary. Afterward, the girl excused herself for an errand she had to run and left on a bicycle. Hanna then said he, too, had to be on is way, although he hated to leave.

“I will escort you part of the way,” the elderly woman said, “and show you the best path to take.

About a kilometer from her house the woman stopped. “See there, right where this little path turns to avoid that old (saying its name in Chinese) tree that has spent a long time getting its roots around that large rock, “ she said. She gestured to a modest-sized tree that to Hanna looked a bit like a gnarly old olive tree whose tree’s roots were partly exposed and wrapped in what could be a strangle or an embrace around a large chair-sized smooth shale grey rock. “My neighbor, Lao Ma, told wonderful stories of the that tree and that rock, about how at first they did not get along because when the tree was just a seedling the rock felt threatened by its close presence. The rock, he said, worried that the tree’s roots would dislodge him from place and he would be sent rolling helplessly down into the river below.”

Hanna’s mind played a video of the rock tumbling and flipping in the air for over a hundred meters and ending with a huge coffee-colored splash. But he could see that the roots had conformed themselves to the shape of the rock, twisting around its contours and then re-entering the hard packed soil. “That must have been some time ago, by the look of things now,” he said.

“Long ago. Old Ma said that the tree and the rock were like this when he was a boy, and that his father had told him the story. At first, as the tree grew, it tried to push the rock out of the way, his father told him. But then the tree saw that some other trees on its side of the path were leaning over to the down slope of the mountain, and some were eventually blown over by the wind. He noticed that the rock prevented him from leaning over, and actually supported him against the force of the wind. Very slowly the tree began to extend its roots around toward the front of the rock, not to push it away, but to get a better grip on it.”

Hanna wondered if this story, which was tending towards a parable, was going to end in another of those inevitable “the Chinese have a saying for such things” endings.

She continued. “The rock, being older, wiser and more indestructible, noticed the growing embrace of the roots, but made neither complaint nor compliment. The rock was old enough to know that the rains that took away a little of the soil each time they came would one day loosen his hold upon the earth and he would, like many other rocks like him, end up at the bottom of the river. He knew that the tree’s roots, extending deep into the earth, would hold him to it.”

“Ah, it’s sort of like the story of having a tiger by the tail,” Hanna said.

“Not really. The rock and the tree became more like friends who come to depend on each other. The tiger and the man remain adversaries.

“Yes, I understand what you mean. And the force pulling the rock and the tree together are in the opposite kind of relationship.” Hanna said.

“My granddaughter calls it symbiosis.” But maybe also it is a metaphor for the relationship between China and America, do you think?” She asked in a tone that indicated she had already given the question some attention.

“Let me guess: China is the rock. Do I have that right?”

“China is over five thousand years . . .”

“OK, and along comes this merely two hundred-year-old seedling that thinks Plymouth Rock is the only rock that really counts. Yes, I will admit that we have been a rather brash tree, but the rock of China has not been very steady in it own soil if I might risk offense by saying so.”

“Well put, professor. Perhaps that’s why it is a good idea for a relationship something like . . .” she gestured to the rock and the tree. We can hope. China is making more of America’s products, and that money is helping to improve China’s standard of living . . . for some at least. It’s a beginning.” She lifted her eyebrows in signal for some assent.

“And you, excuse me, I mean China, uses those monies to purchase some of the debt America is using in its ‘tiger by the tail’ relationships elsewhere in the world,”

“So the symbiotic relationship is already established, do you think so?

“As Rick said to Captain Renault: ‘I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.’”

“Rick?”

“Forgive me, please, I was making reference to a famous American movie, called Casablanca. Have you ever seen it?” The woman shook her head “no.” “It is set in Morocco during the Second World War. A great love story, but it also proves that friendships are often more complicated than love affairs. The rock will outlive the tree, but eventually the roots of trees will, as they must, break down the rock, sapping its minerals and . . .”

“Please lower your voice, Professor; I would not want the rock and the tree to hear such things, especially when they do not have much longer in the warm sunshine on the side of this mountain.”

“Sorry, sometimes it’s best to just let a metaphor be a metaphor, and not some death struggle between biology and geology.”

“We should continue walking now,” the woman said, “I will go with you as far as the house of Old Ma.”

“I would like to meet Mr. Lao. Can you introduce me,” Hanna said, not considering that the man might not speak English.

“That will not be possible, Professor. Lao Ma is dead. He died the day after they painted a red line on his house.

____________________________________________________________

(UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 8.11.2009)

The photographs in this story are from the work of my friend, architect Pauline Shu, who was a Fulbright Scholar in China in 2001 and whose work was exhibited as “Documenting the Dammed” in San Francisco at he San Francisco Main Library, November 6, 2004 to February 5, 2005.