© 2010, UrbisMedia, Ltd.

I consider myself fortunate that I never regarded my occupation as “labor.” I never regarded it as “work” either (although it involved effort), or a “job” even though I was paid as a professor for over three decades. I pretty much regarded it as “what I do,” and what I really liked to do—read, write, and teach about cities and urban life, and get paid for it.

I got a little reflective on that taxonomy the other day when the pretty barista at the café I frequent asked me what I was going to do for Labor Day (no, she wasn’t hitting on me). “Pretty much what I do most days,” I answered, and went out to my table where I usually read and make notes, and pondered that since I retired I no longer have any “seasonality” in my life. No more waiting for the new students to arrive, and all the anticipation of the beginning of a new semester. Now I really work for me.

“Retired” doesn’t quite fit me either, else why would I be at this computer and not playing golf or sailing. Some might say that just don’t know how to relax, or what to do with myself; but I would strenuously object because I know exactly what I am doing, and it’s damn relaxing. I am doing my best to make sure that today is different than yesterday and tomorrow will be different than today.

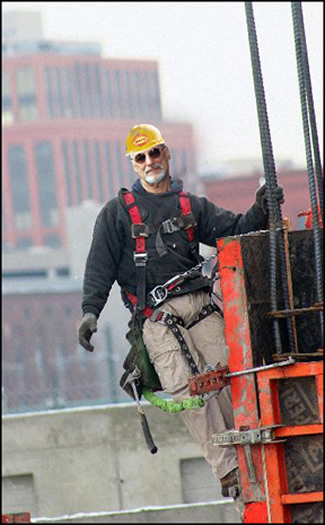

I did do “labor” once. I drove trucks and I was a construction worker and a steel worker. Those were summer jobs and they were supposed to help get me ready for football, but their real influence was to convince me to stay in school. I had to join the Teamsters in order to drive a delivery truck. It was my first union, and the induction oath was something like: “if the brotherhood ask you to park your truck on your mother, you will happily comply.”* Well, I exaggerate a little. But the pay was good. The construction unions weren’t quite as Hoffa-like, and their pay was quite good.

But I learned that I am not good at taking orders, not from lame-brained bosses or shop stewards. I learned that they like to abuse students as much as blacks and “guidos” just off the boat. We all got the crap jobs. And I learned how hard it is to spend eight hours a day ripping up my shoulders hauling steel reinforcing rods.

I have, fortunately, never been in the ”corporate” world. My daughters have told me what that is like—sort of like Glengarry Glen Ross, but not as cheerful. I wouldn’t last a week before I would have to answer for the assault charges. Indeed, probably the variable that most convinced me t retire from the university was that it was inexorably being taken over by corporate mentality. [There’s plenty on this in the DCJ Archives, but cf. especially 65. 2: On Teaching and Learning 4.21.2010]

Work in America has changed relatively quickly. Initially a country of farmers, fishermen and herdsman, they are now a small fraction of the labor force. If women were in the work force (but not counted as such) they were farm wives who were often worked to predecease their husbands. But by 1920 we were more urban than rural and industrial rather than agricultural. But manufacturing employment has been flat for the past forty years and the major form of work is in services. The only education that used to be necessary is what your father taught you; now you need a graduate degree. Yet we retain that myth of the yeoman farmer, master of his own fate and fortune, even when agricultural is the most heavily government supported and regulated “industry” in the country.

This is a country that dumps on its workers. We had slavery until 1864 if you need a benchmark about how we felt about human labor. Our country was founded on slavery, child labor, working women to an early death on farms, and whenever we could, opening immigration to keep labor costs as low as possible. Forget all the bullshit about what a wonderful economic system and government we have, because it took a horrendous war and strikes and political battles for the American worker to get to what is proving to be a rather brief period of some respect and prosperity in the country. All but gone are the days when unions could guarantee a wage that allowed ne breadwinner to buy a home, have health insurance, and send a kid to college.

Call it the Middle Class or the American Dream, it has been being rolled back for the last thirty years, since Reagan’s union busting, and now laid low with the sucker punch delivered by de-regulation and Wall Street—call it what it is—robbery of the American worker. The courts, particularly with the addition of Roberts and Alito, notorious corporatists, to the Supreme Court, so that workers rights and work conditions have been regularly eroded. If the outsourcing of American jobs is any indicator American corporations are bound to the return to slave wages.

But you don’t see American workers in the streets. They are very (or have been made to be) dis-organized and atomized by the fragmentation and diversification of the workforce (office workers don’t understand assembly-line workers). That is just the was American corporations like it. But worse, sufficiently large numbers of American workers are kept appropriately stupid enough to act politically against their own interests. Manipulated by their bigotry, their insecurity, and fear, they will think they are being patriotic when they support any military adventure against any “them” they have only the vaguest knowledge about. Many will support libertarianism because they think government and taxes are their real enemy, or at least the closest and most easily demonized, not knowing it is a fool’s bargain.

The present administration is putatively pro labor. The “stimulus package” was helpful but woefully insufficient and there is not the courage to at least triple it because the deficit decriers—who neither know nor care about the immense destruction that is being brought to many American families, costs that cannot be numericized in the budget—hold the day.

So Labor Day has sort of a Memorial Day feeling now. Sort of like remembering and revering something that is dead and gone—the American Worker. If that is an apt characterization, there was no “enemy.” He was killed by friendly fire.

____________________________________________________________

©2010, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 9.10.2010)

*I was also a member of the construction and steelworkers unions and later joined the professor’s union in California.