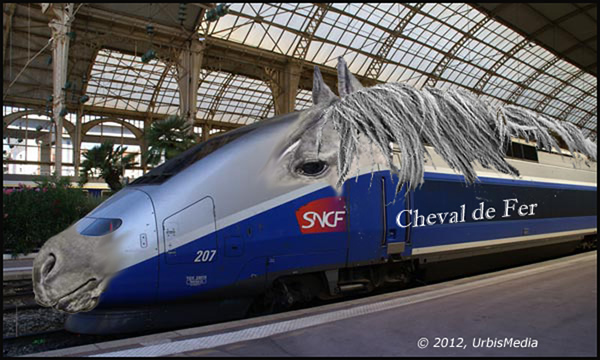

These days the image that springs to mind when one thinks of French trains is that of the TGV (Train a Grande Vitesse). The sleek silver and blue 185-mph passenger trains that whoosh between Paris, Lyon and other major cities and adorn French travel brochures. They are the thoroughbreds of the chemin de fer, with rakish noses reminiscent of supersonic aircraft. Like Japan’s Shinkansen they are in fact a hybrid of train and plane, banking in their turns, accelerating with ‘g’ forces, humming with their quiet power so that one can hear the wind on their skin as they “fly” at zero altitude.

These days the image that springs to mind when one thinks of French trains is that of the TGV (Train a Grande Vitesse). The sleek silver and blue 185-mph passenger trains that whoosh between Paris, Lyon and other major cities and adorn French travel brochures. They are the thoroughbreds of the chemin de fer, with rakish noses reminiscent of supersonic aircraft. Like Japan’s Shinkansen they are in fact a hybrid of train and plane, banking in their turns, accelerating with ‘g’ forces, humming with their quiet power so that one can hear the wind on their skin as they “fly” at zero altitude.

TGVs have a lot of vitesse, alright, if you’re going from Paris to Lyon. But if you’re headed for some place that you actually had to scour the map to locate your train will more than likely resemble one of those oozing steam in one of Monet’s impressions of Gare St. Lazare.

I had been invited by one of my colleagues at the University of Paris to spend a long weekend with friends at his 18th century manor on the Île de Brehat. But when I checked with SNCF, the French rail system, I was informed that it would take three different trains just to get to the coastal town across from the island just off the north shore of Brittany. The agent gave me a Gallic shrug when I asked about the train connections.

“Est-ce possible?” I inquired.

“Je croix que oui.” He tilted his head and made that Gallic pout that often precedes the little “pooht” sound the French frequently employ for added inflection. Translation: “don’t blame me if you end up in Portugal.”

There was no direct or quick way of getting to the Île de Brehat from Paris. The longest leg would be on a train from Paris Montparnasse station to St. Brieuc, with a good many stops in between. From there I would take another, more local, train to Guingamp, where I would switch to a train that is not run by SNCF, but some small local railway. That would take me to Paimpol, near the coast, but I would still need to take a local bus to the village of l’Arcouest, where—finalement—I would board a ferry for what looked to be a short trip to the island. The coast where the D-Day invasion took place was further north, but I figured that if the invasion had used local transit the Wehrmacht would still be lounging in Paris cafés.

I considered aborting the whole trip and lounging the time away in Paris cafés myself; but I knew I would regret missing the chance to see someplace new and perhaps have a little adventure. So I boarded the first train, early in the morning, departing Gare Montparnasse with the commuters to the southwest of the Paris region.

Twenty-five minutes out of Paris most of the commuters had been distributed and my car was sparsely settled with a few old-timers and some school girls I imagined to be heading to somelycee in a country manor. I had just made myself comfortable with a cup of decent coffee, a cigarette, and the International Herald Tribune when, at a stop in Dreux, the car suddenly filled with a motley group of teen-age boys in a state of agitation, jerking and twitching, and making, quick, raptor-like surveys of their environment. My notes at the time say the following: difficult to discern whether these guys are being pursued, or in pursuit; smiles awkward and nervous; maybe they didn’t have tickets or passes and are concerned that the conductor might arrive; but at the same time they seem to need to express some attitude of domination over the car, switching seats every few minutes, they punch and poke one another, chin themselves on the luggage racks, light cigarettes and snuff them on the floor. The atmosphere seemed charged with testosterone.

Some of this display was obviously for some of the schoolgirls in the car whom they didn’t seem to know. I’d been on trains on this route at other times when school kids came aboard, and they socialized a great deal. This was different. I checked out the adults in the car. They seem to have come to a state of alert, watching the nine, leather-jacketed guys over the tops of the newspapers and through sideward glances.

But the young rowdies were primarily interested in the girls. They made some very idiomatic wisecracks I didn’t understand, but that made a couple of the girls hunch down in embarrassment. After a few such remarks, one of the girls fired something back and they laughed mockingly. Some of guys did the usual crotch-clutching and other body postures they mistook for manliness. Then, with simian lumbering, they returned to punching and shoving one another. They seemed to hover somewhere between the need to mate and to destroy, the perhaps not too unrelated infinitives of their awkward immaturity.

Were they really tough kids, or kids acting tough? It was hard to tell. We were after all, in the suburbs of Paris now, but the southern ‘burbs’, not the industrial banlieue of the north where one might encounter really tough kids from working-class, immigrant families. One minute these guys seemed like a pack of sharks, the next they seemed slightly confused and indecisive. Like most packs, they took their bravado from their numbers. I wondered what my reaction would be if they wanted to challenge somebody, maybe me. My mind generated a quick multiple choice: Be the civil guy, and try to reason and calm them down? Try to take the first guy out and hope the rest would panic? Get my ass kicked? All of the above?

I settled for putting on what I call my “city face”. That’s the expression one puts on to deal with the threatening anonymity of the big city. It’s a practiced visage that gives the observer a look somewhere between insouciance and “don’t-mess-with-me-motherfucker.” Actually, it is an expressionless face, a face that indicates its wearer knows where he is, and where he is going; it’s a face that looks through, not at, the eyes and face of those it encounters.

I’ve read articles by former muggers who said they could tell who would be a good victim by the type of face they were wearing: people without “city” faces. There has even been research on the subject that showed that people who come into the city on the subway to work actually put on such faces when they get off the train in the city. They are also less likely to respond to verbal encounters. I had long ago come to the conclusion that a “city face” could also be useful as a “traveler face,” a face that would make one less of a mark for hustlers and other predators on travelers and tourists; the trick being to try to maintain some attitude of openness and amity but without suggesting “how’d you like to rip-off of my camera and passport.”

My city face reflection glared back at me from the window as I tucked my bag beneath my seat, adjusting my posture to enhance my size and quickness. A couple of the guys came down toward my end of the car, hopping in and out of seats, looking for what I couldn’t tell. One made eye contact, took in my best city face, which I then pointed into the newspaper disdainfully, and they went through to the next car.

These French punks prompted a reverie. Several years earlier I had been leading a group of graduate students on a tour of Italy. We had been staying in Sorrento and were returning to Rome. From Sorrento this required a ride on the local railway, called the Circumvesuviana, which corresponds with the Central Station in Naples for the national rail link to Rome.

A similar incident occurred on that occasion. The Circumvesuviana is much like a commuter train, with double doors that open directly to platform level. It stops all along the Amalfi Peninsula and at one of the stops not far from Sorrento four young men entered the car. We had piled our luggage in the seats closest to the door so there would be no delay in our unloading. We were already a little nervous from when we had arrived at Naples a few days earlier and been virtually surrounded by gypsy kids who stalked our luggage like jackals looking for a stray. Now the four young men stationed themselves in the area near the doors, lighted their cigarettes, and somewhat more surreptitiously, examined our luggage.

It surely occurred to them, and was not lost on me, that it would have been an easy matter for them each to snatch a bag just before the doors were about to close and be off down the platform before we could do much about it. And so commenced a bit of choreography as I and a couple of the younger men in our group got up from our seats and proceeded to occupy, along with the suspicious young men, the space near the doors of the car. We also lighted cigarettes, chatted and joked, and exchanged stares with the young men. At each station one of us would step just outside the open doors, preventing an exit with one of our bags.

After several stations it became clear that this was precisely what the young men were intent upon as they became more agitated, and, I think, challenged by our obvious awareness of that intent. In time, however, it became a bit of a joke, and they started returning smiles, and finally, I offered them American cigarettes as a sort of truce. Still we retained our defensive posture, but when they finally exited at a station near Torre Del Greco one of the guys gave us a big smile and a ‘thumbs up’ as the train pulled away from them.

The incident on the French train ended similarly. The two guys who had gone into the next car came rushing back and the bunch of them fled through the doors at the other end of the car. A few minutes later I saw them cavorting on the platform as the train rumbled on toward St. Brieuc and I wiped off my city face. I made a mental note to find out something about Saint Brieuc, once I found out how to pronounce the name. At the time, when I tried to pronounce it, his (her?) name sounded like some sort of runny French cheese; maybe he (she) was the patron saint of the fromageries of this region. It turns out that he was a 6th C monk who founded the abbey that became the town.

At St. Brieuc, I switched to a well-worn local that took its own good time covering the thirty-two kilometres to Guingamp. My fellow passengers had the look of locals about them. Their clothing was unsophisticated and utilitarian, they carried bundles or cheap satchels, and their French had a strong tone of dialect. They at first seemed slightly wary of me, but quickly returned smiles.

When I switched trains again for the thirty-six kilometers northward to Paimpol, I sat directly behind the engineer and felt more like I was aboard a bus rather than a “train.” It behaved like a bus, too, stopping frequently at small villages and at places where there were no buildings whatsoever, not even a siding. The car smelled of animal dung (some people brought their dogs aboard), and the brown vinyl seats were cracked and little more than benches. But I liked this “train”; it almost seemed like it knew where to go on its own from working this route for so long.

At Paimpol I could go no further by rail and took a local bus that wasn’t all that different than my last train, for the short trip up to the coastal village of l’Arcouest . The last segment was the ferry, actually a medium-sized cabin cruiser, carrying a family, myself, and a loquacious English bank manager on holiday. I perfunctorily responded to his interrogation about Southern California, which he said he was considering for a future holiday, as I scanned the shoreline that is appropriately named the Côte de Granit Rose.

The tides in this region of the Channel are some of the most extreme in the world. Although this apparently was not the season for their most pronounced variation it was evident as we approached the port of the island that, depending upon the season and tides, one could disembark at one end or the other of a slanted quay that extended a good hundred yards out from the port. One could easily see that there were colonies of barnacles not only at elevations of ten to fifteen feet from one another, but also well up the red granite cliffs surrounding the port.

The ferry docked about midway up the quay. Not much further on there were numerous boats resting on their keels in the rocks and mud. We were met on the quay by one of the local “taxis”. Since there are no motorized vehicles on the island other than tractors, the local taxis consist of a cart drawn behind whichever one of them is available at the time a ferry arrives. The bank manager and I and our luggage sat uncomfortably in the cart as it jerked us up toward the port. For an instant I had the feeling of what it must have felt like for those luckless souls ferried from the Conciergerie to the guillotine in the Place de la Concorde in horse-drawn charrettes in the bloody days of the French Revolution. But I was about as far away from Paris, at least environmentally, as one could get in France.

The return trip was uneventful. In the compartment of the last leg I dozed off. As we neared the Paris region I awoke to find an interesting couple sitting opposite me. The young man had that Gallic angular face, the same shape, same hair line as the French skier Jean-Claude Killy, the same wide-set eyes that threaten to become Sartrian in old age. His hands were manual labor hands, veined and rough, and a badly rendered tattoo (a dagger with something wrapped around it, maybe a snake) adorned one forearm. On the other rested the head of the baby of maybe four to six months of age.

It was his attitude toward the baby that summoned my curiosity; it was one of adoration, attentiveness, and a hint of vulnerability. Paternity seemed so inconsistent with the rest of him.

She, on the other hand, appeared indifferent, or maybe just exhausted. It was too difficult to tell for sure. Southeast Asian by my reckoning, maybe Indochinese, but she seemed too big to be Vietnamese or Laotian. On further consideration she might have been a Pacific Islander, as the face was straight out of Gauguin: sleek black hair, thick, sculpted lips, and almond eyes.

Incongruously she wore factory-faded jeans, and a black leather jacket, a uniform that a lot of young Indochinese were wearing in France in those days, in such contrast to when Gaugiun brought faces and figures like hers to France on canvas a hundred years ago.

Such an odd couple, these two, sort of an ersatz contemporary Holy Family on their way to some industrial Nazareth in the northern suburbs of Paris. I looked at their faces, his angular and sharp, hers soft and rounded, and wondered what the conjunction of their genes will result in as their child matured. Maybe the baby sensed my thoughts and attention, for began to howl. It’s face reddened and its bellows exerted as much authority in the cramped compartment as would a quarter-ton Sumo wrestler.

The father glanced up at me as he turned the child over to its mother. His expression was blank. I forced myself to look out the window as she opened her jacket and lifted her T-shirt. It was now dark outside, causing the window to mirror her as she manipulated the extruded brown nipple of her small breast into the child’s mouth and it quieted.

Paris seemed like “home” as I reflexively boarded the No. 91 bus from Gare Montparnasse back toward my flat. I recognized this “homecoming” for the relative sensation it was, but it felt good. It confirmed that Paris had become more familiar to me. I switched to the No. 27 bus without even thinking about it.

I had missed Paris, not just because it is Paris, but also because of its universal ‘urban’ attributes. In the city we are in some sense ‘strangers’ to most all of our fellow ‘urbanites’; on the train we become “fellow travelers,” anonymous, but for however long the trip entwined in one another’s destiny.

____________________________________________________________

© 2007 and 2012, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 5.29.2012)

Parts of this story were originally published in Clapp, The Stranger is Me: Travels and Self-Discoveries (2007)