When trains first became a mode of intercity travel they opened a new world to those who could afford to travel in them. But it was still a time, before the advent of photography and the motion picture, when the prevailing imagistic recording of new technology was still painting and print-making. That chronological reality may have something to do with the reason that trains achieved such a romantic appeal amongst modes of locomotion. Hence, it seems appropriate to examine the forms of artistic imagery that were contemporaneous with the arrival of the train.

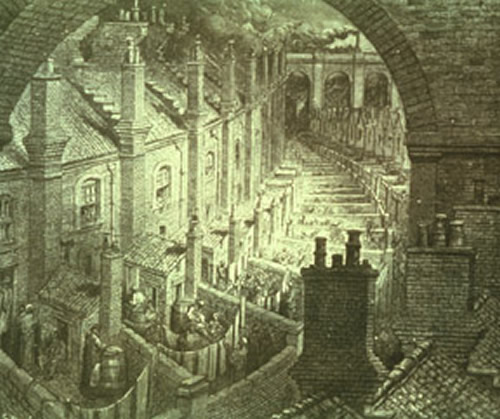

Gustave Doré, “OVER LONDON BY RAIL” (1872)

Part of the romance of the train owes to the fact that the steam engine, perhaps more than any other technological development, symbolized the application of intellectual power to the harnessing of the forces of nature. It expressed in the fusion of the four classical elements of nature—earth, air, fire, and water—a controlled unleashing of natural forces to produce unprecedented mechanical power. The principles of steam power had been demonstrated as early as Archimedes and, in England, as early as 1712, steam-driven pumps were in operation. By the late 1700s Watt’s improvements on the steam engine were applied to transport, including shipping.

But the steam engine had one of its most significant impacts upon urbanization in its application to the steam locomotive. Not only did it make possible the more rapid and efficient movement of goods and bulk materials, but it also offered, in the rapid development of the railroads, a major advance in the conquest of the fundamental characteristics of the natural world—time and space. In J.M.W Turner’s “Rain, Steam and Speed” the sensation of rapid movement through space is transferred to the viewer. This painting, one his biographers notes, “. . . brings out clearly the way in which [Turner] expressed Time as a necessary aspect of his grasp of a changing universe. The forward rush of the engine is expressed by making the engine darker in tone and sharper in edge than any other object, so that it shoots out in aerial perspective ahead of its place in linear perspective. Thus oppositions in tone and line are used to express succession in time.”1

J.M.W. Turner, RAIN, STEAM & SPEED (1844)

In addition to linking its factories with distant sources of raw materials—a factor which permitted greater concentrations of industries closer to their markets in the urban centers—the railroad brought nearby villages and towns within the orbit of commutation of major cities. More prosperous workers were able to enjoy the advantages of industrial concentration while living in the cleaner, more commodious countryside, thereby contributing to a physical separation between the social classes.

By the mid-19th Century, railroads had spread to the whole of Europe, making possible the emergence of cosmopolitan travelers far exceeding in numbers those of the Grand Tour. The romantic adventure of new people and places reached with unprecedented ease at the breathless speed of fifty-five miles per hour was open to those who could afford a third class passenger ticket as well as the wealthy riders of luxurious coaches and dining cars.

The origins and destinations of the rail network—the great stations and train sheds—added a new architectural element to urban imagery. In John O’Connor’s “Pentonville Road” the Gothic spires of London’s magnificent St. Pancras Station and Hotel rise like a vast medieval cathedral into the evening atmosphere. To the right of the spires of Sir Gilbert Scott’s terminal hotel extends the great train shed designed by William Barlow. The less elegant King’s Cross Station is barely visible at the end of Pentonville Road.

John O’Connor, PENTONVILLE ROAD, LOOKING WEST, EVENING (1884)

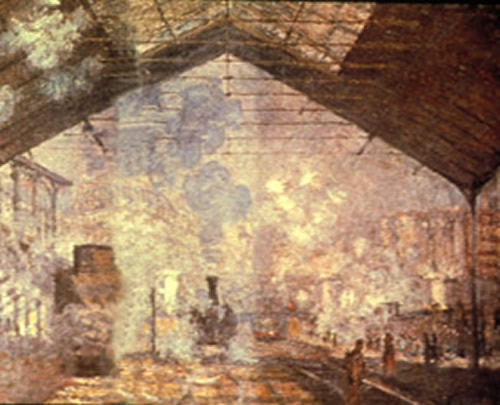

The bustle of activity, hissing steam and lacey steel and glass architecture of the great train sheds inspired several artists. Monet found the play of light amidst these elements worthy of a series of paintings at “Gare St. Lazare” in Paris. This painting, reminiscent with its prominent dark locomotive at the center of Turner’s “Rain, Steam and Speed,” views out to the city through a steam-thickened atmosphere. Hermann Pleuer’s more representational view of the arched steel and glass “Main Hall Old Stuttgart’s Railroad Station” [Fig. 6.21], in 1905, shows well-attired patrons awaiting an arrival or departure.

Claude Monet, GARE ST. LAZARE (1877)

Hermann Pleuer, MAIN HALL OF THE OLD STUTTGART RAILROAD STATION (1905)

The great stations inspired literary artists as well. For E. M. Forester’s heroine in Howard’s End, each station seemed endowed with a special mystique:

Like many others who have lived long in a great capital, she had strong feelings about the various railway termini. They are our gates to the glorious and the unknown . . . In Paddington all Cornwall is latent and the remoter west; down the inclines of Liverpool Street lie fenlands and the illimitable Broads; Scotland is through the pylons of Euston; Wessex behind the poised chaos of Waterloo. Italians realize this, as is natural; those of them who are so unfortunate as to serve as waiters in Berlin call the Anhalt Bahnhof the Stazione d’Italia because by it they must return to their homes. And he is a chilly Londoner who does not endow his stations with some personality, and extend to them, however shyly, the emotions of fear and love.2

Other stations have been immortalized by literature and history: St. Petersburg’s Nikolaevsky Station, the setting for the first parting of Anna Karenina from the swashbuckling Vronsky; the dramatic return of Lenin to the Bolsheviks at Finland Station in 1917; and the countless partings of wives, lovers and soldiers caught in the vortex of the great wars.

But, as railroad networks expanded to bring within the orbit of major metropolitan centers erstwhile remote and small towns the train occasioned more commonplace drama. Camile Pissaro’s view of the arrival of a tourist-loaded train at “Dieppe illustrates the emergence of “pleasure trains” that brought Parisians refreshing weekends by the sea.

Camille Pissaro, DIEPPE (oil) (1892)

Today, in the age of the airliner and he immediately available in which snapped from one’s iPhone, neither the plodding click clack of the rails nor the slow process of an impressionistic painting seem relevant to the frantic pace of contemporary travel. More and more, we care about getting to our destinations by the most rapid form of conveyance, and even our intercity trains my in their comfort and speed the jets with which they compete. And, as it has so often happened in the past, our artistic expression of “getting there” follows suit, or follows not at all.

____________________________________________________________

© 2012, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 9.6.2012)

*This essay has been adapted from the author’s book manuscript, The Art of Urbanism; Cities and Urban Life in the History of Painting.

1. Lindsay, Turner, His Life and Work, New York: Harper and Row

1966.P. 202

2. New York: Knopf, 1951, P. 16