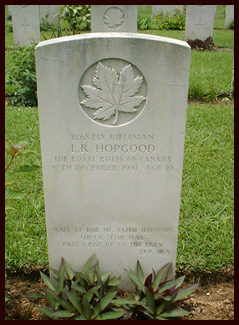

British War Cemetery, Hong Kong © 2001, UrbisMedia

Over nearly 30 years of escorting various groups of Americans to thirty or so foreign countries I have had some unusual requests. Most of them I have been able to comply with (with the notable exception of that defrocked priest who wanted to sleep with me).

In an earlier travel memoir I wrote of my fascination with cemeteries when I travel, of the way that different cultures deal with the ultimate trip (the one without a return ticket, unless you’re a Buddhist or Shirley Maclaine). I have visited many cemeteries all over the world, often searching for the final resting places of people, good and bad, of renown, people I know only from their historical reputations. It’s a curious way of getting “up close and personal,” I admit.

In 2001 I was giving a preliminary lecture to a group of Americans I was to escort through a three-week China trip when a woman in the group asked me if it might be possible to find the grave of her brother when we arrived to Hong Kong at the end of our tour. She was at least in her late sixties and had not seen her brother since the day he left their home in Eastern Canada in 1941. He was Leslie Hopgood, at the time a 19-year-old volunteer in the Royal Queen’s Rifles.

Hong Kong had been invaded and conquered in the space of a few days just after their surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. The British Crown Colony was expecting to be attacked, but was ill-equipped to fend off the powerful Japanese forces. Hong Kong is where Leslie Hopgood was headed with the rest of the Royal Queen’s rifles.

I was to be in Hong Kong for some weeks before heading to Shanghai to meet my travel group, so there was a chance to see if I might locate his final resting place. I began with the Canadian Embassy, which, strangely, seemed to have no records of the locations of the servicemen in Hong Kong. It was the British Embassy, after being routed to several people, who directed me to a Jack Edwards and provided me with his phone number. I left a call with his secretary and was surprised when I got a call back from him in less than an hour.

“Did you say Hope good, or Hopgood?” he asked me. I could hear some pages being shuffled in the background. “Leslie?” you said?

“Yes, sir, Leslie Hopgood.”

“Right, I have him. Royal Rifles. Killed in action December 19, 1941. Can’t have been here more than a few days before he went down,” Edwards added. “I think I could show almost the exact location where it happened. There’s also a Sergeant Clayton, who would have served with him and lives in Canada. Could put you in touch with him.”

I was surprised by such accuracy of information, but told him that I was trying to locate his grave for Hopgood’s sister, who would be in Hong Kong in a few weeks.

“Sai Wan Bay War Cemetery, Port 8, Row C, Grave 9 from the Left, go straight down the main aisle from the front of the cross,” Edwards instructed as though he knew the place by heart. He did, and seemed to know everything else about Hong Kong in WW II as I learned in the forty-minute phone conversation that ensued. For Edwards the war in Asia was no thing of the past; he spoke of it as though it had ended last week. He maintained an organization that kept just the kind of records he had just provided me with. He didn’t want anybody to forget what had happened and was somewhat of a fixture around Hong Kong, especially on occasions when commemorative services were held.

In searching for Leslie Hopgood I ended up learning much more about Jack Edwards, a Welshman who served in Malaysia, where the British were also ill-prepared for the Japanese onslaught. Edwards ended up a POW of the Japanese, and he will never, ever, forget, or forgive what they did to him and his fellows. Captured in Singapore he eventually ended up in a POW camp in Taiwan where they were brutalized and forced to be slave labor in a copper mine. They were flogged, starved, tortured, ravaged by dysentery, and died by the hundreds. Edwards stayed in Asia after surviving the Japanese to continue the fight, this time to get the Japanese to own up to their brutality, and get the British to give the POWs and their families the benefits to which they were entitled. It’s all recounted in his book, Bonzai, You Bastards!which he wrote forty years after the war.* It took years, but he was successful in getting the benefits awarded and was himself awarded and O.B.E. for his long service.

The war cemetery is at the east end of Hong Kong island, up in the hills above Chai Wan it slopes down toward the eastern entrance to Victoria Harbor. I went there before I would escort Hopgood’s sister there a month later, to make sure I knew the way to his grave. As I looked down over the neat rows of headstones, many of them marked “A Soldier Known Only to God,” I had the thought that at least these men who has reposed in this well-kept cemetery for over sixty years had a nice view of the sea. It’s silly, but it’s very Chinese, very feng shui . It must be the reason there are so many cemeteries on these slopes. Was that any consolation to a guy who never made it to his twentieth birthday, who has been in this ground since I was a year old, and who will be here forever? Cemetery thoughts.

I was glad Leslie Hopgood, and the rest of these British fallen had Jack Edwards to look after them until he joins them. It gave me a good feeling to see his sister stand tearfully in front of his neatly-preserved resting place on that hillside in Hong Kong. Like me, and like Jack Edwards, I suspect that she takes some comfort in that this boy with such a tragically short life will always have a nice view of the sea.

___________________________________

©2006, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 5.31.2006)

*Edwards told me during our phone conversation that he could have had his book published by a major publisher if he had been willing to change its title to something less provocative. He refused. As it happens there is a Japanese edition with the title Kutabare Jap Yaroh, which contains a “very rude expletive.” Addendum 2016: Jack Edwards has since passsed away and was sent to join those he helped keep in remembrance, with full military honors among olther accolades.