Americans Abroad No. 7

Author among the Pharaohs ©1991 UrbisMedia

Nubia, Upper Egypt, 1991. Putting it as charitably as truth will allow, the domestic airlines of Egypt don’t inspire confidence in even the most insouciant of flyers. The ZAS Boeing 727 that I boarded looked to be in reasonable condition. Despite the fact that, in high season, they are regularly jammed to capacity, this plane was clean and didn’t have the broken seats and stained and torn carpeting one might expect on some regional Aeroflot equipment.

But when, what I first took to possibly be a romanization of Arabic script on the emergency information card turned out, on closer examination to be Polish, my blood pressure ratcheted up a few points.

My first thought was that I was on a plane that probably was no longer considered serviceable by a Polish airline! The Egyptians apparently had a higher confidence in this castoff Polish airliner than I. Maybe they even felt that not bothering to translate emergency instructions into Arabic, or at least English, lent some prestige to their service. My own Polish vocabulary, which is exhausted after “please,” “thank you” and “where is the toilet?” gave me to wonder what the hell fix we would be in an emergency evacuation of the plane. Unless the pilot and co-pilot happened to be Lech Walesa and Pope John-Paul II we would definitely be in deep doo-doo.

The other unnerving aspect of ZAS is that their computers (maybe also Polish discards) have this disturbing way of deleting some names from their record. As a result, the group of 27 I had booked on the flight from Aswan to Abu Simbel fluctuated between 26 and 11 each time I checked it. On the day we were supposed to fly it was 14, leaving me with an unappealing Solomonic choice of telling half the group they couldn’t go, or canceling out completely.

I cancelled. But there were a dozen people who wanted desperately to see the magnificent temples at Abu Simbel. The option that remained was to see if I could rent a van and a driver for the three and a half-hour drive through the desert. I found an air-conditioned van that would accommodate the determined dozen and we set off with our driver, whose English vocabulary was double my Polish vocabulary, around the Aswan Dam, into that part of Upper Egypt that used to be called Nubia.

The imprudence of my consent to this project came crashing into my consciousness a few miles after we had passed the military checkpoint, if one can call two pathetic soldiers standing by a guard box on the blazing tarmac two-lane road a checkpoint. They were the last humans, and their guardhouse the last structures, we were to see for a good two hours.

It soon became evident that the purpose of a mirage is to relieve the eye of the monotony of a landscape devoid of distinguishing features. The 120-degree heat radiated from the two-lane tarmac road, occasionally covered with drifting sand. To our left, somewhere beyond the horizon undulating with waves of super-heated air rising from the dunes was Lake Nasser, the huge water body formed by the Aswan Dam that turned the ancient land of Nubia into an Atlantis. To the right were seemingly endless, and trackless dunes and drifts of the Sahara.

A little reflecting on these facts and it would become apparent to a reasonable person that it wouldn’t take too much to go wrong for us to end up in a heap of trouble, or worse. Such potentials must have occurred to others, as I saw some of them hugging their water bottles a little more tightly.

This atmosphere was enhanced by the fact that after some two hours of driving we saw no other vehicles moving in either direction, until our driver flagged an oncoming truck carrying a few camels in its open bed. When we got out to take some photos of the camels it was like stepping from a food locker into a sauna. Our eyeballs dried out, our lungs felt seared and we dashed back to the tenuous cocoon of our air-conditioned van like frightened chicks to a mother hen. If we required proof that an engine failure, or a broken belt on the air compressor, almost any mechanical malfunction, could be our undoing, we had it now. With no cell phone, or any roadside emergency communication equipment, we would have to rely for help, if any, on the luck of a rare vehicle happening by. Judging by some of the gallows humor some of us began to banter around I wasn’t alone with my grim imaginings.

Even our driver seemed a trifle relieved as we sighted the town near the temples. It was late in the afternoon, and the temperature had dropped a few degrees, moderated by our proximity to Lake Nasser.

Our driver rousted the caretaker of the temple site from his siesta, greased him with some of the Egyptian pounds I had supplied him, and we were admitted to the magnificence of the temple precinct.

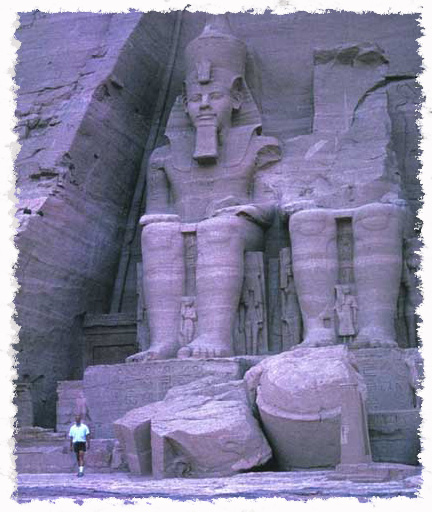

Whatever tourists might have been to the site that day were long gone. With the sun low in the sky gilding the enormous statues, the millennia seemed to roll away and we were alone with the astounding splendor of the monuments to Rameses and Nefertari and their gods.

The very scale and magnificence of Abul Simbel has been matched by the fact that these two temples, carved from Nubian sandstone have been excised out from their original site and relocated in a concrete-constructed sixty-five metres above the waters of Lake Nasser. In the 1960s it took a French, Italian, Swedish and German team of engineers four years and $40 million to rescue them from certain inundation when the Aswan dam was completed. All the risk of getting here seemed well worth the privilege of our private audience with the great Pharaoh and his Nubian queen.

Even though we were returning in the dark, the desert air seemed as hot as when the sun was high in the sky. The air-conditioning was still running full blast. Now there was virtually nothing to be seen that wasn’t illuminated by the van’s headlights, and the superheated black night air opened briefly before us and closed behind us as though we were traveling through the gut of some giant creature.

About half way back to Aswan we saw some light coming from the only structure we had seen on the entire length of highway: a two-car garage-sized building composed of cinder block. It was closed when we passed it on the way in, but now the front was open, showing itself to be the Sahara’s equivalent of a 7-11.

The driver asked if we need any maya (water), and since we could probably still dehydrate even though it was nighttime, we suggested he stop. The air was still sauna temperature when we got out of the van. This was Upper Egypt’s idea of a roadside service area: an 80-watt bare bulb illuminating some shelves of tinned meats, snacks, cigarettes, and a selection of beverages. Two men sat drinking glasses of tea and sharing a water pipe. They were fully garbed in galabiyyas and turbans, but probably cooler than we were in our shorts and t-shirts.

In the almost pitch-black desert night this little outpost of dim-light and scant refreshment seemed like a tiny asteroid in the vastness of space. Without ambient illumination there was only what light came from a clear starlit sky that we’d almost forget existed behind our smoggy urban canopies.

We bought the place out of their inventory of maya and drove off into the ink of the Sahara night. [to be continued]

___________________________________

©2005, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 5.11.2005)