One of the very first phrases that are learned in my high school French class was a response to the simple salutation, “Comment allez-vous?” The (presumptuous) response offered in my text was, “Je suis content.”

One of the very first phrases that are learned in my high school French class was a response to the simple salutation, “Comment allez-vous?” The (presumptuous) response offered in my text was, “Je suis content.”

“I am content, or I am pleased.” Maybe “content” carries a different connotation for the French than the tinge of resignation it seems to convey en Anglais. Indeed, since I cannot recall ever hearing it uttered by a Frenchman, “Je suis content” might well be as archaic it sounds, an almost Proustian or Flaubertian sentiment. Certainly, as a high school student with most of my life before me, all my desires and ambitions yet taking form, and my testosterone raging for release, mere “contentment” seemed far too little to settle for. It was a time when one felt more “in process,” under development, a project reaching for high achievement, virtuosity, self-possession, gratification, and that most slippery and ineffable state of being—happiness.* Mentally, I reserved “contentment” for something to be experienced with the souvenirs of pleasant memory in a rocking chair on a porch in a salubrious summer afternoon in my “sunset years.” That would be contentment.

Later, in my university years I came upon a related term, not one that I would dare employ as a response to “how are you?” The almost psycho-babble “self-actualization” would qualify as a state of being well beyond contentment. This Mazlovian** level of personal intellectual and circumstantial elevation, seems a secular equivalent to that of Buddhist enlightenment. Respond that you are, or feel, “self-actualized” at a cocktail party and you are likely to be spending the remainder of the evening talking to a punch bowl; give that response at a bar, and when laughing subsides, someone will probably ask you whether you think the Green Bay Packers will be self-actualized this year.

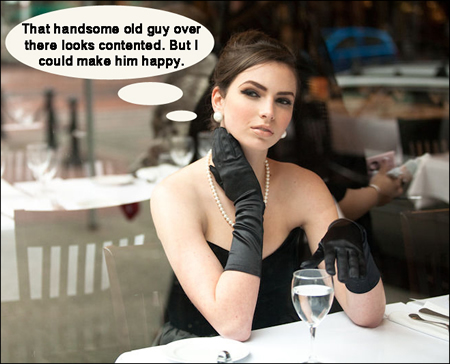

Yet, if it ever was a statement of being in common use, contentment would have long been surpassed as a desired state by “happiness.” But this latter term seems far more sublimated and elusive than contentment, with more than a suggestion of a state of perfection. If I am asked by someone, “are you happy?” my mind always seems to summon the response: “Why? Do I look happy?” Happiness has always seemed to me an emotional peak, an evanescent state of bliss with the warning of lurking disappointment. When I hear someone make the statement that “life doesn’t get any better than this,” logic compels the recognition that it can therefore only “get worse.” While we all have experiences that we can recall as being the best time of our lives, it seems more an affect of the present age than it is the default state of being. Having recently overheard at the café a young person greeted by a friend and asked how he was, and answered unhesitatingly “I’m pretty excellent,” I could only wonder at the very idea of so casually superlative a life.

Yet, I should not be unfamiliar with the notion of contentment, as contentment is something that is built into the very liturgy of Christianity, and in particular Roman Catholicism. In that context, contentment is a nasty, insidious notion of social control. In its religious expression contentment takes on a fatalistic resignation whereby religious authority endeavors to persuade its subjects that a) their circumstances are part of God’s plan, and b) the endurance of them is part of their earned merit for an eternal reward. Such contentment is to be accepting of one’s circumstances however dire, as well as to be unquestioning of those who have been the recipients of divine beneficence. God does not obviously apportion earthly contentment in equal measure; ergo, there must be an eschatological pay-off for those who are screwed in his ”plan.” Sure.

Here is a context of contentment for me: out on a sunny Sunday in Rome (other cities, too, but let’s just stay in Rome for now, as it is likely to be sunny and it’s my favorite city). I have with me the essentials for contentment—a good book, my camera, my notebook (to jot down pithy pensée on such things as contentment), my phone (in case I want to call somebody and tell them that I’m feeling kinda content), my iPod, a fresh cannoli, and a perfect cappuccino at the terrace of a café at, say, Piazza del Pantheon. That’s contentment for me. Happiness would be if the gorgeous girl sitting across from me was straddling my lap and sucking on my tongue. [OMG, I can’t believe I wrote that! What impure thoughts got into me! You should never put stuff like that on the Internet; NSA is taking this all down. Obama will read it! Impressionable youth might “stumble” on it when they are typing “porn” in their browsers!] OK, I just put that in there as a little treat for those who read this far.

But if contentment denotes only what one will “settle for” in life then it might not be such a good thing. To be content is a form of stasis, a state of satisfaction with things “as they are,” the status quo, thereby over-whelming the restless, even dis-contented, spirit that is sometimes requisite for creativity, a mentality that might push us to a new level, an attitude of dynamic disequilibrium that seeks risk and adventure—even putting at risk contentment itself.

Still, one wonders how the world might be a better, more peaceful place if more of us would settle for contentment. Would American Idol contestants be content to settle for second place (or just screeching those God-awful Motown songs in the shower); would life be all that diminished if your favorite team didn’t win the Super Bowl, or the Final Four; so what if you can’t afford that (ugly) Louis Vuitton handbag, or granite counter-tops in your kitchen makeover; won’t a Honda Civic get you to the hospital just as quickly as a Beemer (and shouldn’t you be caring more about the quality of your healthcare anyway). Maybe acceptance of contentment would result in less war, intolerance, poverty, and sickness and disease in the world. Should we be content when so many others are circumstantially “discontented?” Then, again, should we perhaps be examining how much of our contentment is hydraulically related to those who have far less of it than us, none at all?

So, Est-ce que je suis content? Not necessarily. And maybe I shouldn’t be.

_______________________________________________________

© 2013, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 7.4.2013)

*I recently read The Geography of Bliss: One Grump’s Search for the Happiest Places in the World, by Eric Weiner (2009), but he never seemed to get around to the question of how much happiness could be achieved by just “getting laid.”

**Abraham Maslow, “A Theory of Human Motivation” (1943)