I came to America because in the old country I had heard that the streets of America were “paved with gold.” But I learned three things after I arrived: First, the streets were not paved with gold. Second, the streets were not paved at all. And third, it was I who was going to have to pave them. [Story told by many immigrants]

This posting begins a multiple-part series on one of the major political issues of the present day, and one of the major factors in the development and character of America: immigrants and immigration. The series is adapted from my forthcoming book, The American City in the Cinema (Transaction, 2013). See also in the Archives of these pages No. 31.8.

L’America

As tough and ungilded as American city streets might have been, they never lost their allure for those to whom they represented the chance for a better life. For many, especially in the nineteenth century, that chance began with their first sighting of the Statue of Liberty in New York’s harbor. It is an image Chaplin employed in The Immigrant (1917), and it has been reprised in numerous films since. In the opening sequence of The Legend of 1900 (1998), steerage passengers, assembled on the aft deck of an ocean liner, are engaged in preparations for their imminent disembarkation. The narrator intones over their activities that there is “always one” of them who is “the first,” to get a sight of it. At first there is a sense of disbelief, and the words catch in his throat, as though he is waking from a dream. Then, as though the first one to sight land after a long voyage of lost souls, he calls out: “L’America!”

The arrival of young Vito Andolini (renamed Vito Corleone by an impatient immigration official) inThe Godfather: Part II (1974) is less dramatic, but Coppola employs the first sighting of the statue to heighten the emotional effect of arrival.

One of the most compelling scenes of arrival occurs near the end of Elia Kazan’s autobiographical America, America (1963). Virtually all of this film takes place outside the United States, in Greece and Turkey, but the “promised land” is never out of mind, especially in the obsession of the protagonist, a twenty-year-old Anatolian Greek, Stavros (Stathis Giallelis), with immigrating to America. America, America lends documentary support to the gravitational power of America’s image to oppressed peoples. Upon his arrival, Stavros falls to his knees to kiss the hallowed ground in gratitude. On being told that he should cut the almost clichéd gesture from the film, Kazan justified keeping it in, saying, “I doubt that anyone born in the United States has or can have a true appreciation of what America is.”1

However, arrival in America has not always been a glorious event for immigrants. The passage through Castle Garden, and later Ellis Island, could be undignified, as chronicled in the mustering scene in Chaplin’s The Immigrant and the screening and medical examinations in Hester Street(1975), America, America, and The Godfather: Part II. Names were changed, quarantines imposed, motives questioned, and some were denied entry and repatriated. Well before the current thrust of Homeland Security’s more rigorous scrutiny in the post-9/11 climate, there were immigrants whose arrival was unpleasant and illegal.

Cinematic treatment of the smuggling of would-be immigrants into America, especially of those whose chances, owing to quotas or discrimination, would not likely gain legal entry, dates at least to the 1930s. In I Cover the Waterfront (1933), Chinese being smuggled into a West Coast port are chained and thrown overboard when the Coast Guard approaches, presaging contemporary practices in which Chinese are smuggled in shipping containers, often arriving dead or, if alive, indentured for years to pay off their smuggling costs.2

However, it is worth mentioning that feature films about immigrants and immigration fell off during the interwar years, as did immigration itself. Not only was international travel perilous during the wars, but the Depression, as well as a more xenophobic and isolationist spirit among Americans between the wars, appears to have affected the box office prospects for movies that dealt with the subjects of immigration and assimilation.

Thus, I Cover the Waterfront was exceptional in this regard. But even by 1948, My Girl Tisa,a film starring Lilli Palmer as an immigrant girl in New York, which touched all the aspects of the turn-of-the-century immigrant experience, failed at the box office. Americans, adjusting to postwar conditions, were not ready for nostalgia about the days of immigration.3

The Founding Fathers of American Cinema

Still, the ungilded streets of American cities were where immigrants often found an economic foothold. In one of the early scenes of Ragtime (1981), a piano player watches pictures on a silent screen and causally fits his music to first a one-reeler and then some newsreels. A few scenes later, in recreated busy streets of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Jewish immigrants are plying various trades from stands and pushcarts. One of them, Tateh (Mandy Patinkin), makes his living cutting silhouette profiles for sitting customers. Later, he is seen peddling the flip-books he makes to shops, and in still later scene he reappears in a beach scene, this time directing a one-reel silent film with actors in costume.

The year was 1910, and the notion that a peddler might quickly rise to become a movie director is not only a plot convenience, but also an historical gesture to the early days of the cinema in America. Indeed, in the early years of the twentieth century, the conditions for the emergence and growth of the American cinematic experience might have been unique in the world. The cinema also took root in Western Europe, at the same time, and quickly spread to Asia. But in America, the city, the cinema, and immigrants came together at this time in a unique and unprecedented way. Immigrants were involved in the creation of the American cinema as audience, were often the subject matter, and installed themselves in production and distribution. The portrayal of a Jewish immigrant peddler as an early American filmmaker is more fact than fiction.

Hollywood was created by a remarkably homogeneous groups of Central and Eastern European Jewish men. . . . It was they who transformed primitive moving pictures, the product of very recent technical advances by Edison and others, into America’s most popular entertainment form by the early 1920s. Nickelodeons were replaced by movie palaces (sufficiently opulent to satisfy the escapist needs of the working class and to capture the respectable middle class), short flicks expanded into features, their obscure players made into stars, and eventually, by the late 1920s, their visual pleasures enhanced immeasurably by sound.4

The founders of the great movie studios were Jews who had emigrated from the villages in Germany (Carl Laemmle), Hungary (Adolf Zukor and William Fox), Russia (Louis B. Mayer), and Poland (Benjamin Warner). The men who became the moguls of the movie industry had no special training or talent for that line of work. They were unlettered and some of them were barely literate. But they were skilled in trades that were suited to the needs of the early film enterprise; they were used to methods of merchandising that brought products to consumers.5 Early film distribution, to beer halls and social clubs, and then to nickelodeons, was suited to men with experience as peddlers. Thus, the storefront theaters that exhibited films before 1920 were subsequently transformed into movie theaters by these men who knew how to conduct business in the city, where getting the product to the consumer was, in the initial years of movies, key to its success. Realizing the promise of this enterprise they quickly moved into all aspects of production, forming talent agencies, hiring entertainment lawyers, and, of course, with their movement to the film production friendly climes of California, founding their own industrial city: Hollywood.

They were unlikely men to leave their imprint upon the American city. The cinema not only changed the way in which Americans found their diversions and entertainment, it also introduced a new land use to the city. Cities had theaters since the golden age of Greece, but they were few in number and usually centralized. Large, opulent movies palaces would be built in the centers of American city, but the cinemas would also proliferate and become a fixture for many years in different neighborhoods, until new methods of distribution came into being.

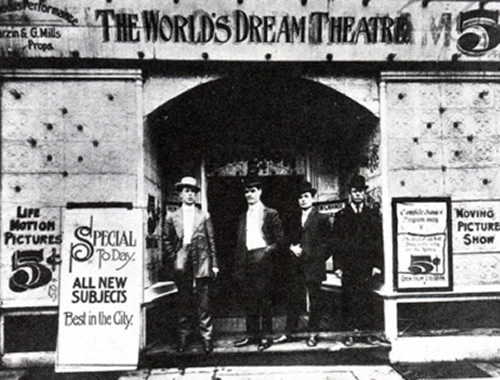

An early Nickelodeon theater and its proprietors.

These unlikely founding fathers of film did more than establish a new industry; they left their imprint on the industry’s product as well, especially in the way it was used to portray life in their adopted country. Extremely conscious of anti-Semitism and concerned about accusations that their domination of the industry would undermine American values, they made great efforts to appear as American as possible. As a result, their films created a varnished, wholesome image of the country—a place that was far more tolerant in their movies than it was of them. Although they craved assimilation, they associated mostly among themselves in a social world of their own making. Hollywood allowed them a certain respectability that would not have been possible in the Eastern establishment, and where there were no social barriers to admission in a business that was new and not regarded as the equal of other professions. Thus, in a strange way, the cinematic vision of America, certainly in the formative years of the cinema, was created by entrepreneurs who were outsiders, not only as immigrants, but also as men who continued to regard themselves as outside the mainstream of American social life.6

[To be Continued]

____________________________________________________________

© 2013, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 2.8.2013)

1. Wake, n.d., .) America, America (Review), http://www.culturevulture.net/Movies2/AmericaAmerica.htm

2. As with Africans, many Chinese were also brought in against their will. Chinese women, for example, were sold, or “Shanghaied,” to be smuggled to West Coast cities to be unwilling brides or to supply brothels (Yan, 2001). The economic exploitation and physical mistreatment of immigrants, often as much by their former compatriots as by their new hosts, continues at borders around the world. In contemporary Southern California, New Mexico, and Texas, for example, illegal immigrants are often found dead from dehydration in the desert or suffocated in sealed trucks, left abandoned by their transporters or coyotes; The Border (1982).

3. These same decades did much to breakdown the world of colonialism and unleash a tide of immigration that would wash across many developed nations; it continues to the present day. With the subsequent breakup of the USSR and the Warsaw Pact nations, a further wave of immigration was set in motion. Hence the number of films treating these populations both as subject and audience increased markedly in the period since the 1960s.

4. Zipperstein, Steven (1989) “The Lions of Judah in the Jungle of Hollywood,” The Los Angeles Times Book Review, November 5, Pp. 12

5. European Jews might well have become skilled at peddling their wares from carts and stalls to consumers because in many countries they were either not allowed to own property, or otherwise found owning real estate a risky investment when expulsions or pogroms were threats.

6. Gabler, Neal (1989) An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews invented Hollywood, New York: Anchor Books, Introduction