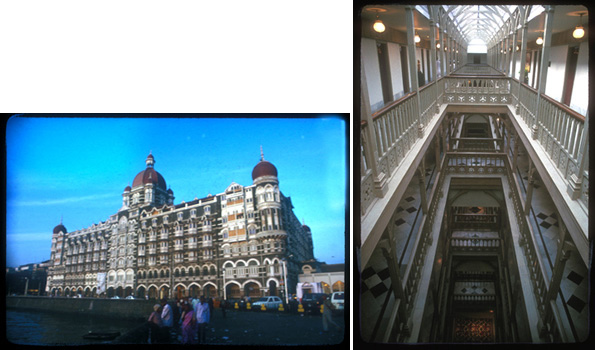

In 1992, my dear friend, Sue, and I flew into then Bombay (now Mumbai) from London on December 6, for a few days before taking ship to other Indian ports and eventually to Hong Kong. We transferred to the magnificent Taj Mahal hotel, beside the historic “Gateway of India” seen in these photos. Later, we transferred over to the Oberoi Hotel on the west side of the peninsula that Mumbai occupies.

Views of the gateway Arch to India from hotel room at morning and evening

Seeing these two hotels again, in the news, and besieged by terrorists who killed more than 150 people was a reminder of our own brush with terror in that visit sixteen years ago. Whether or not that incident, reprised from a posting I made in these pages on 01/07/2004, is related to the historical antipathies in India that continue to plague the country, is yet to be determined, but it is clear that, for all of its rich and fascinating cultural stew, India remains a country that can turn violent as quickly as a monsoon rain storm.

View from room in the Taj Mahal Hotel, and magnificent interior atrium design

Bombay Jihad (December 1992)

The last thing I would have thought as the huge sewer pipes rolled ominously toward my taxi was that I might be done in by a dispute over a land use. After all, this was Bombay, and the land use at issue was nearly a thousand kilometers away in Ayodhya.

But this was India, and the land use was a mosque, one reputedly built on the site of the birthplace of the Hindu god Rama in 1,500 B.C. Never mind that the mosque was built over it only thirty years after Columbus discovered America. Like I said, this was India, and disputes go back a long way in these parts. And so do the antipathies over which god or goddess is the rightful resident of a piece of holy ground. The current controversy was precipitated when 4,000 fundamentalist Hindu “kar sevaks” pulled the Babri Mosque down with their bare hands yesterday, and now there were aftershocks all over India.

Fires were already burning in several parts of Bombay, in one of the areas of “chawls,” where tens of thousands inhabit these ancient and rickety tenements at incredible densities, and in the teeming shanty-colonies that through squinted-eyes and pinched-nostrils, are indistinguishable, visually, olfactorily, and, socially, from (un)sanitary land-fills.

People were already dead, slain as much by religious bigotry and hatred as by the knives that are the preferred implement of dispatching their victims to Allah or to another round of Hindu reincarnation. Casualties of a holy land use war.

“Go for it!” I encouraged the driver, who seemed to be considering abandoning his taxi and fare as hundreds of others already had. So he weaved between and around the huge sewer pipes that could have crushed the taxi like a Pepsi can. The irony of it all wasn’t lost on me: in a city that sorely needs some sewerage they use the pipes to block streets and conduct murderous riots.

That wasn’t all. Here we were on my way back from a visit to Gandhi’s house, the pacifist who had several times threatened to starve himself to death to arrest the Hindu-Muslim carnage that took more than a million lives after the British partitioned the sub-continent into India and two Pakistans in 1947. And one of the dioramas at Gandhi’s house showed him being assassinated by a Hindu fanatic who belonged to the Hindu extremist faction that is precursor to the current kar sevaks. Not to mention that me, a lapsed-Catholic, had a good chance of being killed in an officially secular state in a war between two religions. Would it be preferable to have my throat slit by a mob of Muslims, or Hindus? Better not at all.

“Keep going!” I ordered the driver.

In the previous days’ wanderings about this exotic and swollen city it had seemed there was little left to be disputed in the use of its land. In reflection of its social castes, the architecture and land use of Bombay co-exist and juxtapose in astonishing variance. Below our window in the renowned Taj Mahal Hotel reposed hundreds whose beds consisted of littered and feculent sidewalks. Here, and along most of the streets of this bustling metropolis, untold numbers live, eat, copulate, sleep, beg, and die, alfresco.

The Taj Hotel, like the Victoria Terminus train station, and the University of Bombay radiate the Gothic splendors of the departed British Raj, cheek by jowl with deity-festooned Hindu temples, and pitiable enterprises countless street vendors. On the west side of town splashy high-rise modern hotels garland the magnificent corniche of Chowpatty Beach, interspersed with derelict buildings and homeless. Soul-searing poverty and hopelessness taint every land use in Bombay. There is nothing, and everything, to fight and die for.

Our taxi pulled into the relative safety of the port the Bombay. The death toll had reached seventy. Only as our ship glided past the Gateway Arch of India did it occur to me that, for so many here there is probably little more to hope for than a better afterlife. It seems like the only hope left in a country that makes jihad over where their gods can reside.

____________________________________________________________

(UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 12.1.2008)

Originally published in the San Diego American Planning Association Journal,

© James A, Clapp, March, 1993. Posted: Wed – January 7, 2004