© 2007, UrbisMedia

When I first began foreign travel over thirty years ago I brought with me a bottle of aspirin. I do remember using them. These days It looks like my suitcase belongs to a “mule” for a Columbian drug cartel. The necessity for such an array of medicaments owes more to the aging process than to the increased hazards of travel. Many people are daunted by foreign travel at the aspirin stage; I seem to push on, at least until my prescriptions push out the final change of underwear.

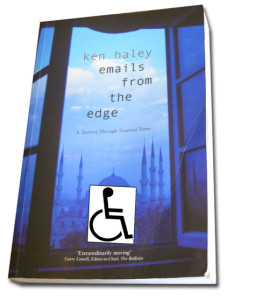

Probably everyone who writes a travel memoir [insert here shameless self-promotion of your own travel memoir] thinks that they are writing about places from a unique perspective. Unless they are plagiarizing from Jan Morris, Bruce Chatwin or Pico Iyer, they probably are; we all see things from our unique perspective. This is what caught my eye about Ken Haley’s memoir. He has, as he says, two perspectives on the places he travels to, one from normal height, the other from the height of his wheel chair. Haley has traveled to over forty countries since his severe spinal cord injury, and they are not easy countries and he has not been on package tours. Haley travels alone. So, if you are a traveler, you are almost obliged to pick up a book by a guy like that.

Haley is a journalist, in both sides of his travel career, abled and disabled. So he has a sense of the story, and in his case he doesn’t expose all of his lead in the very first paragraphs. The reader doesn’t find out—as curious as one must be about it—how Haley ended up in his wheel chair. In the United States, the results of accessibility legislation can be seen everywhere, in curb cuts for wheelchairs, enlarged toilet stalls, elevators, even cruise ship cabins. But in most of the countries Haley travels through in this book one is more likely to become disabled by the lack of those and elemental safety concerns. Just think of trying to do famous tourist sites like the Foro Romano, or the Athenian Acropolis in a wheel chair. Tiananmen Square might be a nice, flat space for the paraplegic, but the rest of Beijing and most Chinese cities are a tort waiting to happen for the most able-bodied traveler.

An Aussie from Melbourne Haley, like many Australians, goes out on “walkabout,” and more recently, “rollabout,” for considerable periods of time. He has worked for newspapers and news organizations in several countries over the years. We pick him up in this book in Bahrain in just prior to what is now called the first Iraq (Bush) war. Haley is noit a clear as he might be in this section, perhaps because it is part of the build-up to what we are most curious about. I maker it out that he finds himself somewhat stranded in Bahrain at the time of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and quite nervous that Bahrain might well be next and he would find himself a captive of Saddam’s nasty troops. That does not happen, but probably because there are other things in play in Haley’s mental state, helped along by some problems with his employer, the author has what can only be called a serious psychological breakdown.

That sort of problem is one that no one would wish to experience even at home, but far from home, in a culture that might not quite understand it the same way, and you can be in real trouble. In rather short order Haley goes from making a public disturbance, to threatening police, to landing in a hospital for people with his type of problem. He may not be so clear about subsequent events because he was not so clear about much at the time.

After his release Haley is clearly not in good shape psychologically, and not, over a hundred pages in he is a depressive insomniac back in Melbourne, but even friends and family seem unable to help him Finally, he can’t take it any more and throws himself from the fourth floor window of an apartment intending to kill himself, but breaking his legs and crushing vertebrae. Haley hoarded pills for a while, intending to finish the job that insufficient altitude did not do, but the long process of rehab seems to have given him time to think his way through his problems. Now he had a new purpose—to see if he could resume his life of travel and writing from a sitting position.

Eleven years after his breakdown Haley is, amazingly, back in Bahrain at the beginning of what at times—maybe it s just because this section of the book reads largely like notes from a travel journal, with too few insights, very often banal and uninteresting. At times he seems more interested in checking places off his “dance card,” and providing information that seems gratuitous, than in the more existential aspects of the travel experience. Sometimes the pace is manic as over the months he travels through, almost exclusively by land, the entire Middle East, and then through the former Jugoslavia, Greece, eastern Europe, Russia and the Baltics.

There might have been more attention to the problems of getting on and off various modes of transit, the inaccessibility of hotels and bathrooms, safeguarding his belongings. There are people who assist him, people who ignore him, and fewer—those infamous border guards and immigration officials–who place obstacles in this path. At one point his suitcase that contains the catheters and other necessities for his health and cleanliness is stolen, on another his money is stolen, but Haley prevails, in surprisingly good spirits and an attitude of “what can you do to me that is worse that what I have done to myself.”

Haley finishes his remarkable journey, in time, space, and mentality, 69 degrees North of the Equator, pushing his wheelchair through the snow in Norway, but not before spending a couple of chapters on interesting self-examination and introspection. I especially liked it when he said, neat the end, that “Like all good journeys, this was one of self-discovery . . ,” almost the exact words that are below the title of my own travel book. This guy has traveled not only to a couple dozen more countries, a few thousand more miles than I have, but he also made that fateful forty-foot trip out of that window. He’s here, as they say, to tell the tale. One suspects there might be some more from this resilient wanderer from down under.

___________________________________

©2007, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 5.11.2007)