©2005 UrbisMedia

Call me Ishmael. I’ve long nursed a desire to go to sea. But, alas, most of the sailing I’ve done is through the pages of the voyages of others. I am constitutionally unfit to serve in the Navy, or wear some silly commodore outfit of a “yachtie.” I did some cruises, but that’s like swimming the English Channel with water wings. I would have preferred to sign on to a Yankee whaler and shout “Thar she blows” from the crosstrees of the mainmast but the PETA people don’t want us harpooning whales anymore; or head off single-handedly to discover far seas and myself like Joshua Slocum or Sir Francis Chichester, but I get lonely. I ached to ply distant shores where I could blend the genes of tawny Polynesian beauties with my Milkamagnesian DNA. Such were the yearnings of youth and the fantasies of middle age, and now, despite having plied the waters of every ocean and the Black, Mediterranean, Andaman, Tasman and South China Seas, I face the prospect of being an Ancient Wannabe Mariner, encumbered with the albatross of other, landlubberly, choices.

So I read a lot of books about the sea.

This review is prompted by my stumbling upon a sea tale penned by that great swashbuckler of the silver screen, Errol Flynn. The adventure recounted in Beam Ends took place before Flynn became a film actor, when he bought an aged, forty-four-foot gaff-rigged cutter named “Sirocco” and sailed out of Sydney Harbor with two buddies, bound for New Guinea, some three-thousand miles to the north. Flynn proves to be a facile writer, and by accounts that are not from the pulp of Hollywood, a more literate and artistic sort than the boozing womanizer most people remember him to be.

Beams Ends is sort of a pelagic road picture where the future “Captain Blood” leads his friends into a series of misadventures as they hug the coast of Australia up through the Great Barrier Reef to finally wreck in the Gulf of Papua on the New Guinea coast. Along the way there is plenty of carousing, various encounters with the “authorities,” but it is related with restraint and a gift for narrative, not the sort of “wild boars gored my loins” adventure travelogue one finds today, or something that would rival Lady Chatterly’s Lover .

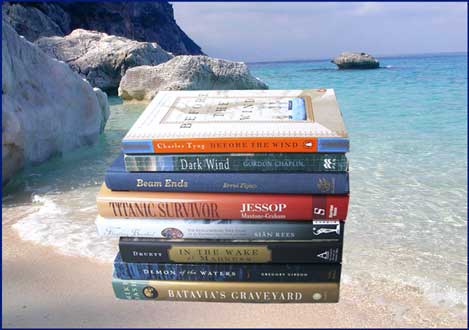

Flynn never lost his proclivity for the momentary pleasures, or his love for sailing and the sea. But unlike innumerable “armchair” mariners he had the audacity to put to sea ill-prepared and later the funds to afford more able vessels. In fact, the sea life was hardly as romantic as would be sailors tend to portray it. Beam Ends turns out to be relatively tame compared to some of the other books I put to sea in recent months. They are worth a brief mention. Charles Tyng’s Before the Wind is a “log” of a New England 19 th Century merchantman withy enough mutinies, piracies, and shipwrecks for several books. Mayhem at sea was not uncommon. Merchant ships were often manned by social misfits and even criminals. Batavia’s Graveyard , by Mike Dask, is a riveting reconstruction of a flagship of the Dutch East India Company that never quite made it to Dutch Indonesia because of a wreck on a barren atoll off northwestern Australia and a mutiny the resulted in the slaughter of many of the passengers.

Whaleships were equally hazardous, not just from the dangers of attacking whales from flimsey little whaleboats, but brutal ship’s masters and crew members who might go berserk from working and living conditions that cause union organizers or OSHA officials to jump overboard. Gregory Gibson drew upon journals of some of the sailors to reconstruct the story of a mutiny on the whaleship Globe in Demon of the Waters that ended in murders and even deaths at the hands of southsea islanders. One is also amazed at how much brutality the average sailor would endure or witness in accounts such as In the Wake of Madness , by Joan Druett in which the savagery of its captain resulted in his own murder and the subsequent deaths of several crewmen.

A different take on the romance of the sea is revealed in Sian Rees’s The Floating Brothel , an account of a ship transporting female convicts from England to New South Wales in the 18 th Century. Transportation (usually for life) was preferable to death for petty offences in England or imprisonment on hulk ships in the Thames, but the long, hazardous voyage caused many women to use what they could bargain with for advantage with the crew of the Lady Julian. Once again, a journal by a crew member is the source of a story of what appears to have been a true, if star-crossed, romance between its author and a young woman convicted of a minor theft.

These days it is possible for more people to set out on their own on romantic sea voyages. Large numbers of couples venture into blue waters well offshore or make long voyages in relatively small boats. But the sea can be unforgiving. Of the several accounts I have read of things going bad is Dark Wind . Author Gordon Chaplin and his wife, Susan, an upstate New York couple in a romantic second marriage for both, set out to sail in the Marshall Islands on a midlife adventure. But the wind does indeed turn dark when they unadvisedly try to ride out a typhoon and Chaplin’s book turns to a journal of therapy at losing his new wife when she slipped from his grasp in a raging sea.

Uneventful accounts being, of course, less dramatic, are less likely to make it into print, in any age. These days most people answer their call of the sea, or casino, or ship’s boutique, or midnight buffet, on cruise ships. Most will succumb to over-eating or drinking, but the most dramatic voyage was that of the Titanic. There are many accounts of that fateful voyage, but the recently published memoirs of Violet Jessop, a stewardess aboard that ship who survived it is especially interesting. One would think that such a brush with death couldn’t happen twice. But Ms Jessop, was serving later on the Titanic’s sister ship Britannic, being used as a hospital ship in the Mediterranean when it, too, was sunk. She survived to pen the record that became Titanic Survivor, some ninety years after the event . She lived out her days in a cottage in England.

It’s best to end with a happy ending.

___________________________________

©2005, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 8.22.2005)